How the establishment tried to censor Andy Warhol without knowing anything about him.

As a hugely inquisitive child during the sixties and seventies, I was more aware of what was going on in society than anyone probably realised. I was no different to millions of other children who are instinctively tuned in to the zeitgeist. How could they not be? We read newspapers, watched telly, viewed lots of films, and most importantly, listened to what adults were talking about. It was all there in front of us. Children are just sponges for culture and I for one resented a lot of the shit that was thrown at me in terms of ‘children’s’ television at the time. I wanted challenging TV, innovative TV, groundbreaking films, the bottom line being I wanted to know what was going on in the adult world. Hence the fact my nostalgia for 60s and 70s TV was for The Prisoner, The Avengers, Monty Python and Marty Feldman rather than Crackerjack, Play School, Blue Peter and any other infantile crap middle-aged, middle-class adults perceived I was going to like. I wasn’t prepared to accept thin gruel.

To be fair to my mum and dad they weren’t the type of parents who felt it was their duty to protect me from the excesses of the grown-up world. I was allowed to watch many classics of the 60s and 70s such as Steptoe and Son, Wednesday Plays and Budgie. I didn’t think so at the time but they were quite liberal. And in 1973 I became very aware that there was a real stooshie brewing in the media about a documentary film that had been made that ‘they’ were trying to ban.

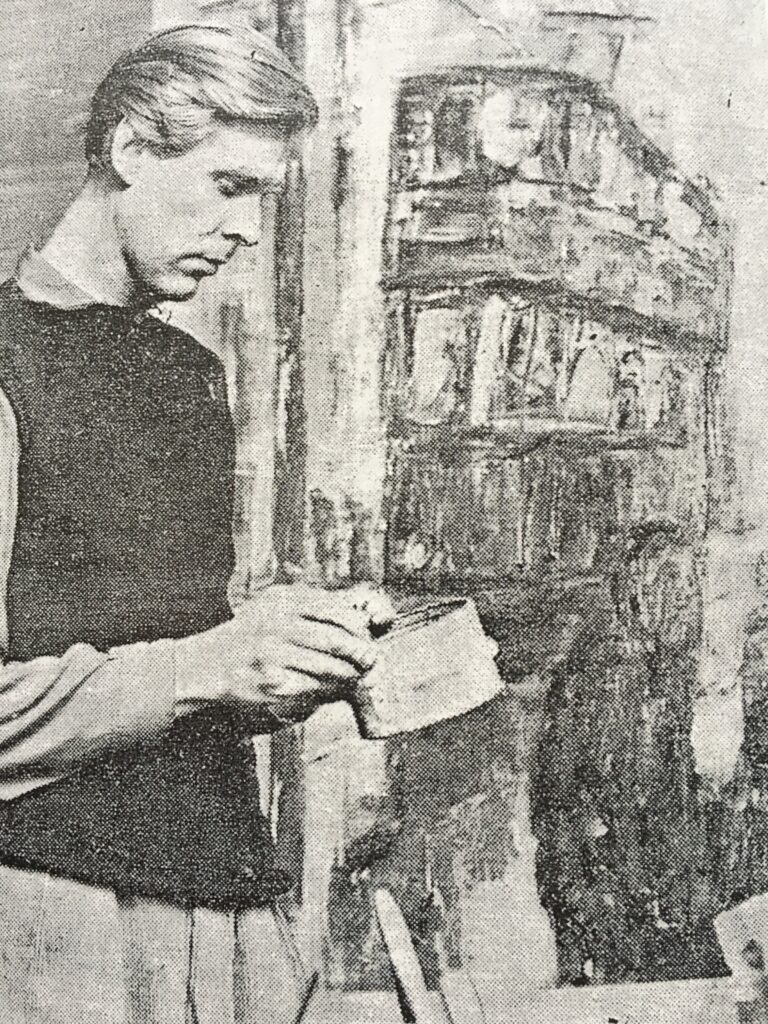

Nothing alerted my curiosity, or anyone else’s for that matter, than when a TV programme was branded ‘shocking’, ‘revolting’ or, even better, ‘offensive.’ And such was the case with British photographer David Bailey’s documentary on Andy Warhol.

I had heard talk of this beast, Andy Warhol. Certain words and expressions surrounded the name like moons around a weird planet. New York, nuts, freak, sleazy, sex films, strange art, scary, threatening society, drugs, controversial. What was not to like? It would be many years before I became completely obsessed with Warhol and his world, but, at this point, I was just desperate to see this film.

The tabloids, of course, could not believe their luck, a heaven-sent excuse to go into moralistic overdrive about a film they hadn’t seen. ‘Judges Halt Sex Film,’ ‘Judges Ban TV Shocker‘ were just two headlines from newspapers that backed Ross McWhirter and Mary Whitehouse’s moral crusade for ‘decency’. Obviously they hadn’t seen the film either. McWhirter and Whitehouse presumably also hadn’t seen the naked teenage page three models in the tabloids or maybe they thought that was just good clean fun. Either way it took a couple of months before those self-styled arbiters of good taste and decency had their banning application thrown out by the courts. And on 27th March 1973 the film was broadcast.

I had tracked the course of this film through the courts during January and February of 1973 and as the broadcast approached I was determined I was going to see it. I distinctly remember the evening of 27 March 1973. It just so happened that same evening The Godfather won Best Film at the Oscars and Cabaret won 8 other Oscars, Slade’s Cum On Feel The Noize was at number 1 in the singles charts, while Alice Cooper‘s Billion Dollar Babies was top of the album charts. So there certainly was a movement away from the mainstream at this particular time.

My dad worked nights at that time and I remember my mum going to bed about 10. She asked me what I was doing and I said, ‘I want to watch that programme on Andy Warhol.’ That was fine with her and she went away leaving me to watch the most eagerly anticipated TV experience of my life on my own. It really didn’t disappoint. It was quirky, it was strange, it had some truly odd people in it as expected and it portrayed an artist who was shy, sometimes monosyllabic, playfully provocative and unique. Was it the ‘shocker’ trumpeted by the tabloids? Of course not. One scene featuring a member of the Warhol entourage, Brigid Polk, showed her on the phone to Andy while she made a series of ‘tit paintings’. This involved her rubbing bits of painted card on her breasts to create images on the card, a bit like brass rubbings, which would probably have pleased Mrs Whitehouse much more. At the start of the sequence we see Brigid throw scraps of coloured paper down the toilet, flush it, then take polaroids of the paper being tossed around by the water. The sight of a toilet probably upset Ross McWhirter more than anything. Or it would have if he’d seen the film, which he hadn’t. It was only 12 years, after all, since Hitchcock was the first film director to show a flushing toilet in cinematic history when he featured it in his 1960’s classic Psycho.

A clip from a Warhol film with two actors discussing having sex on a motorbike travelling at 60 miles per hour definitely upset the moral vanguard. Not because of the language used, ‘fuck’ was still extremely rare on TV, but it was more the fact it would have been a danger to other traffic that worried McWhirter.

So the film came and went. I loved it. It was a serious documentary on a serious artist but it was also funny, we were introduced to a clique of odd people we had never seen, even imagined, before and it gave an insight into a wonderfully seedy world we’d only heard whispers of. Years later my interest in Warhol would be ignited again and I would find out that Warhol’s best and most influential years had been behind him when this film was made and he was heading towards his ‘celebrity’ period, a bit like when a band moved from a cult following to being stadium fillers. They were never quite the same.

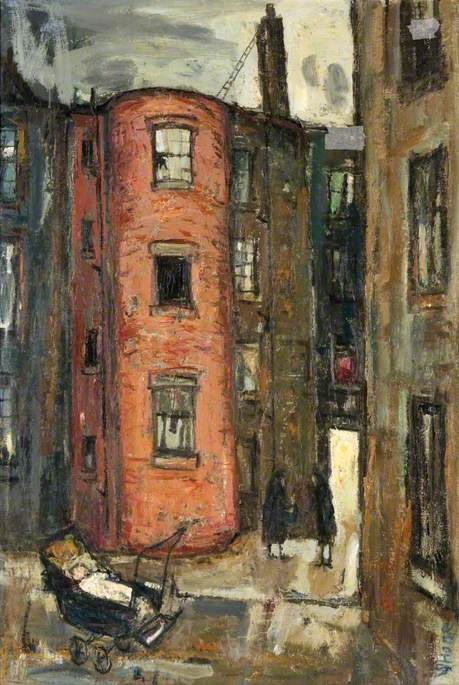

To see how this occurred we have to go back to the early 60s. Warhol had arrived in New York in the 50s and worked as a graphic artist and designer, most notably for Glamour magazine . Eventually he gave up illustration and began to concentrate on his own art and after installing himself in a few workshops around NY he moved into the workspace that established him as New York’s prime artistic mover, the Silver Factory at 231 East 47th Street.

The Silver Factory became Pop Art Central from January 1964 until his lease ran out in late 1967. Any artist worth his or her salt, musical, literary, cinematic, photographic, visual, even political passed through the Silver Factory at some point. Warhol also assembled an entourage of New York’s waifs, strays and oddities who hung around the Factory waiting for something to happen. Despite the strangeness of many of the Factory’s denizens, the copious amounts of drugs around and unpredictability of events, anyone well known visiting NY would head for this otherwise mundane corner of the metropolis. Liza Minelli, The Beatles, The Stones, Tennessee Williams, Cecil Beaton, William Burroughs, Salvador Dali, Allen Ginsberg and Truman Capote, amongst many others, regularly dropped in despite its reputation as a den of sleaze, iniquity and degradation. In fact, that probably encouraged many to visit.

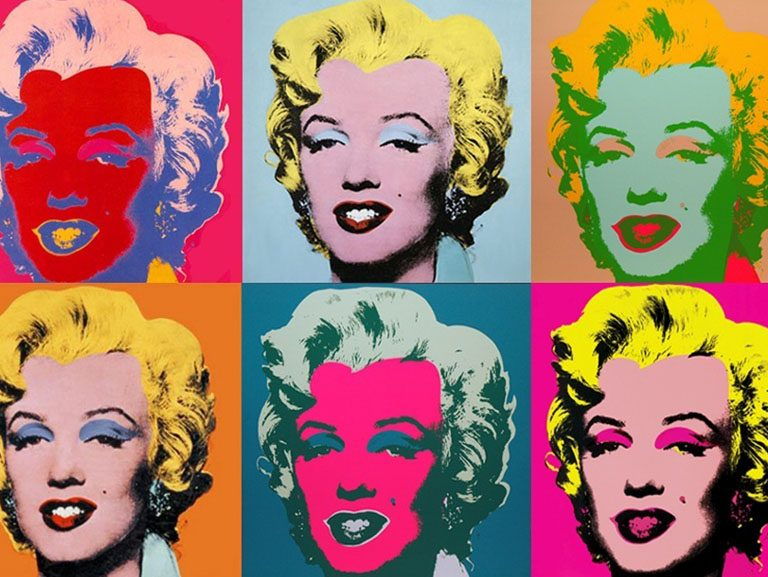

It was here he established himself as one the leading practitioners of pop art. In a frenzied few years of activity he created larges screen prints of Hollywood idols, of Campbell’s soup cans, models of outsize Brillo boxes, even of his floating sculptures, silver flower-shaped balloons filled with air which you see all over now but Warhol invented them.

Warhol also began creating his ‘underground’ films at this time. Starting with ‘Sleep‘ and moving on to ‘Empire‘ where he filmed the Empire State Building for 8 hours and 5 mins ‘to see time go by.’ His ‘screen tests’ of people visiting the Factory, where they had to sit motionless and look at a camera Warhol was pointing became hugely influential with avant-garde and later mainstream cinema. Of the 472 ‘Screen Tests’ which still exist, many are of well known people of the time as well people from the New York downtown scene. I once saw an interview where a reporter tried to get Warhol to explain why his films were called ‘underground’. He clearly hoped Warhol would talk about them being non-mainstream, anti-establishment, sexually graphic, unconventional or something similarly controversial. Warhol just said laconically, ‘Well, uhhh, we make them in cellars and basements. That’s, uhh, probably why.’ He was a master of obfuscation.

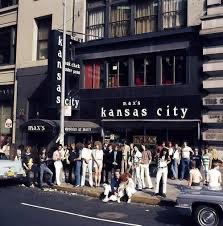

After a hard day’s screen printing Warhol and his entourage of the day would head down to a few blocks to his favourite restaurant, Max’s Kansas City near Union Square. After taking over the back room, Warhol would offer paintings to the owner for the feeding of his guests. On one notable evening Bobby Kennedy turned up at Max’s to have a chinwag with Andy but only stayed a short time as one of his security men spotted the unmistakable aroma of marijuana and quickly whisked him away. After ‘discovering’ The Velvet Underground (for me the most influential band of all time) at Cafe Bizarre in the Village Warhol had them play regularly at Max’s and soon it was the hottest eatery in New York with queues forming similar to those at Studio 54 (a favourite venue of Andy’s) some years later. In 1974 Max’s Kansas City closed temporarily and re-opened as a punk and New Wave music venue featuring legendary bands such as New York Dolls, Devo and Blondie. For those who read NME and Sounds in the 70s Max’s Kansas City was a familiar venue often mentioned along with CBGB’s. Max’s closed for good in 1981 and is now an excellent deli, though a far cry from its 60s and 70s greatness. I know, I’ve been there.

In January 1968 Warhol moved his operation into the 4th floor of the Decker Building on 33 Union Square West, shortly before 231 E. 47th Street was demolished to make way for a new high rise. A much more upmarket building than the dilapidated, dingy loft of the Silver Factory, it coincided with Warhol becoming more business-orientated and having a number people work on his projects rather than just himself and his assistant Gerard Malanga.

On June 3 1968 Andy Warhol was shot in this building by an occasional visitor to the Factory, Valerie Solanas, who was incensed that a script she had written, Up Your Ass, which she had asked Andy to read had been misplaced. Warhol barely survived and when Bailey filmed his Warhol documentary a few years after the shooting, it was a very different Warhol to the free and easy figure of the 60s. In the years following the Bailey film Warhol would transform himself into his next artwork, that of establishment celebrity rubbing shoulders with Hollywood and political royalty. One wag observed, ‘Andy Warhol would attend the opening of a drawer.’ But I feel this was always the long-term project. To show how his 60s anti-establishmentarianism could be transformed into ultimate celebrity acceptance.

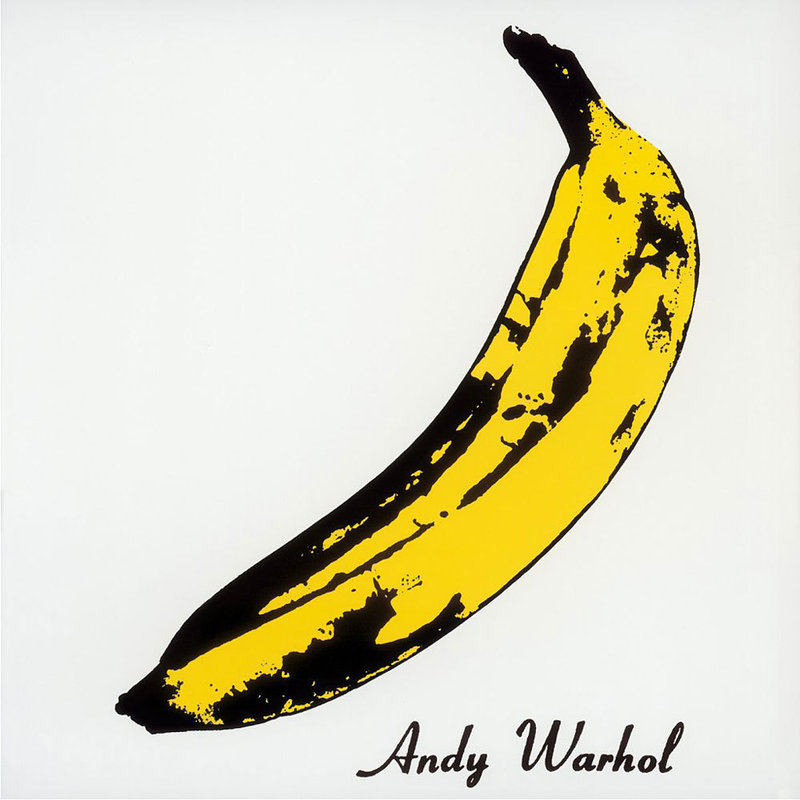

Someone once asked me, knowing my interest in Warhol, why he was so popular as they didn’t think there was much to his work. It made me realise that Andy Warhol was the artwork. Everything about him and the things surrounding him were part of a huge artefact and that, for me, made him and New York the fulcrum of the modern art movement throughout the 60s. Without Warhol we would not have had the grunge, garage and punk, even classical, influences of The Velvet Underground, his films influenced many, many directors to experiment with form, mise-en-scene, sound and narrative, his pop art still influences artists today and his pronouncements which seemed so weird at the time, turned out to be so prescient. Hasn’t everyone become world-famous for 15 mins in our multi-media platform, social media obsessed times? Isn’t art about what you can get away with?

He even designed the Velvet Underground album cover and Sticky Fingers album cover for the Stones and invented the word ‘superstar.’

Bailey’s documentary is still a fascinating study of an enigmatic and still influential totem of pop art, music and cinema as well as being a wonderfully symbolic anti-hero for the 60s. The Bailey film also was a turning point in the public attitude towards censorship and people like Whitehouse and McWhirter knew they were never going to get away with this form cultural fascism again.

Inadvertently, Warhol had changed the cultural landscape yet again, without really trying. And to think people just thought he was nuts.