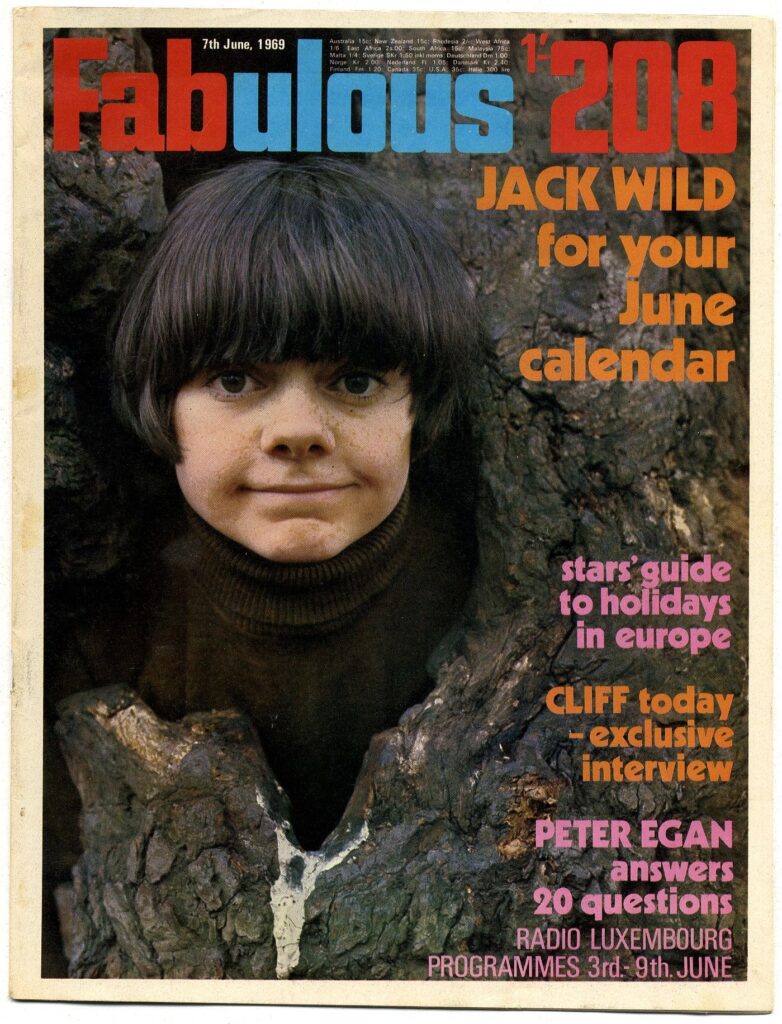

Everyone knew Jack Wild in the 60s and 70s and for a short glorious time he could do no wrong

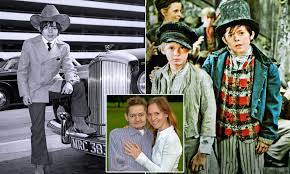

For most people of a certain age, Jack Wild was the quintessential Artful Dodger in Carol Reed’s classic musical version of Oliver!, written by Lionel Bart, in 1968. It seemed the world was Jack Wild’s oyster after this film and it really was. America had awarded the Best Film Oscar to Oliver! and he was nominated as Best Supporting Actor, although this went to Jack Albertson for a film no one remembers called The Subject Was Roses. An American sojourn ensued and Wild appeared in a range of US productions including the weirdly psychedelic HR Pufnstuff. His career trajectory dipped during the late 70s, however, and never really recovered. It was the classic story of too much, too young maybe with drink playing an important part and Wild died in 2006 at the tragically young age of 53. But for a golden period in the late 60s to mid-70s Jack Wild was a household name and his achievements were significant and it is those achievements and career highs this blogpost will focus on, rather than his very sad demise.

Before Jack was catapulted to fame by Oliver! he had had small parts in some highly respected British TV series of the late-60s including Z Cars, the almost forgotten BBC serial The Newcomers and the superb and innovative BBC science fiction series Out Of The Unknown, which was his first speaking part (for the record the episode was Come Buttercup, Come Daisy, Come….).

Despite playing the part of The Artful Dodger and sounding like the archetypal cockney kid from Central Casting, Jack Wild was actually born in Lancashire and moved to London as a child. He was spotted playing football with his brother Arthur by, of all people, Phil Collins’s mum June who was a theatrical agent and this led to him being cast in the London West End production of Lionel Bart’s hit musical about Oliver Twist, Oliver! Although some reports claim he had the title role, he was actually just one of Fagin’s gang but this eventually resulted in him being cast as Dodger for the film. His confident and cheeky demeanour as The Artful Dodger in Oliver! endeared him to the viewing public and before long everyone knew of Jack Wild and the massive success of the film in the US had producers clamouring for his services.

Oliver! changed Jack’s life forever. His role in the film struck a chord with the public and catapulted him to success. For a while at least. He was even nominated for a Best Supporting Actor Oscar. Up against Seymour Cassel for Faces, Daniel Massey for Star and Gene Wilder for The Producers, the award went to the prolific Jack Albertson, a well-known TV face for the almost forgotten The Subject Was Roses. Albertson was probably best known as Grandpa Joe in the classic version of Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, coincidently with fellow-nominee Gene Wilder. I remember him well as appearing in long-running Dr Simon Locke, (alternately known as Police Surgeon) on British afternoon TV during the 70s.

This is nothing new, of course, as British actors who find themselves nominated for Academy Awards or even just appear in a successful TV show always tend to have a short period of stateside success. I’ve already featured the wonderful Judy Carne (See Judy Carne: A Truly 60s Star) in this little blog space and how her US career skyrocketed after she appeared in the American sitcom Fair Exchange. Her TV dad in this show during the early sixties, one of the most well-known faces in British film and TV at the time, Victor Maddern, went on to appear in episodes of top-rated shows Perry Mason and Bonanza on the strength of his short-lived US exposure. Another example, of many, was Jean Marsh who not only helped create but also appeared in almost every episode of Upstairs Downstairs which was massively successful in the US. She went on to have a very successful career in America appearing in big series such as Hawaii Five-O, Trapper John, obviously Murder, She Wrote and The Love Boat. Anyone who was was anyone in the acting business appeared at some time in The Love Boat! In fact it was the US equivalent of Casualty or The Bill. Everyone in the acting profession eventually appeared in it at some point in their career.

Jack’s fame spread like a rash and he was soon courting the chat show kings such as Simon Dee and Johnny Carson. To see Jack Wild’s mature but slightly vulnerable interview here on Genxculture favourite Dee Time ( See Dee Time: When The Sixties Really Began) is really quite fascinating but also sad as we now know what showbusiness traps were awaiting him. But that wasn’t before he appeared in one of the weirdest, most psychedelic, eye-popping series of the 60s and 70s: HR Pufnstuf.

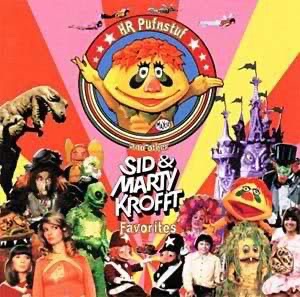

During the premiere of Oliver! in the US, Jack met producers and puppeteers Sid and Marty Krofft who thought he’d be perfect to star in a new show they were developing called HR Pufnstuf. For two series and a feature length film Jack would star in this most psychedelic and weird series. Having been shipwrecked on to Living Island where everything is alive, they are constantly under attack from Witchypoo (Billie Hayes) who wants Jack’s magical flute. He befriends a timid dragon (HR Pufnstuff) who helps him fend off the ruses of Witchypoo and a jolly time is had by all. The garish colours, the surreal setting, the odd narratives and the fairytale, abstract characters all suggest the writers and directors were on something a little more than creative energy. Something the producers, Sid and Marty Krofft, always denied, although possibly less vehemently than one might have expected for the time. And what the hell? It was a terrific and wonderfully weird series and, let’s face it, many of the greatest artistic endeavours throughout the last 100 years have benefitted from a little chemical inspiration. For me, it makes the series even more memorable.

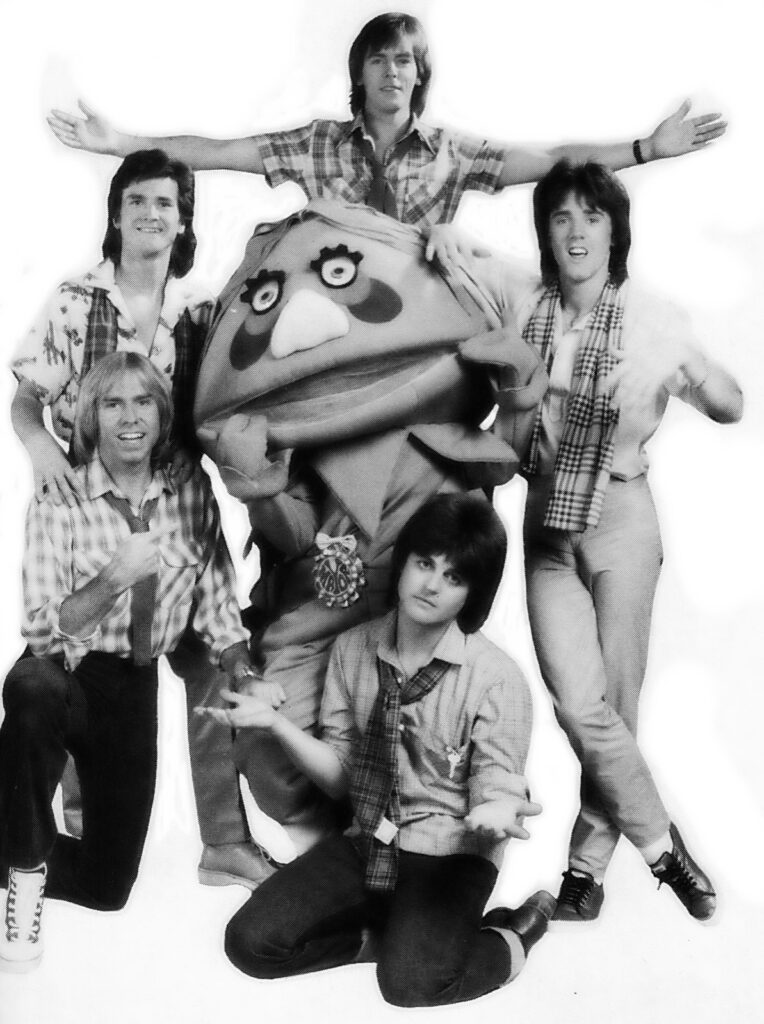

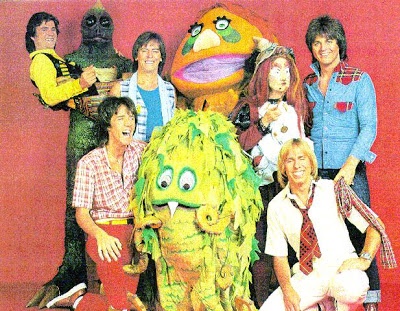

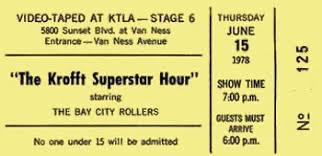

In 1978 the Kroftts created a Saturday morning show entitled The Kroffts’ Superstar Hour for the US. This very successful format included characters from Pufnstuf as well as, believe it or not, The Bay City Rollers! The show eventually morphed into The Bay City Rollers Show which as well as Pufnstuf characters also included The Rollers doing sketches and performing. I had no idea they had their own American show, as well as the awful cut-price Muriel Young produced show in the UK. I wonder what the American audience made of The Rollers’ terrible acting and Scottish accents? We may never know…

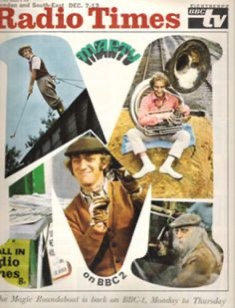

The Kroffts had previously been involved with another iconic 60s series, The Banana Splits which had a similarly scatter-gun approach to narrative, characterisation and mise-en-scene. To be honest, although I watched The Banana Splits on a Saturday morning (there wasn’t a lot of choice in those days), I always felt it was trying just a bit too hard. It was zany and madcap (two words coined by Shakespeare) and although we missed out on the flamboyantly colourful sets, as we still had only monochrome then, it was something different. It clearly had a lasting effect on young viewers though. Everyone who lived through the sixties remembers the theme tune and The Dickies even had a punk-lite hit with it in 1979 reaching a high of number 7 with The Banana Splits Song. As a 9 year-old I always looked forward to The Sour Grapes Bunch making an appearance. They were menacing and intimidating. Unlikely this sort of thing would be encouraged nowadays. Also appearing regularly were The Dilly Twins singing Ta-Ra-Ra-Boom-De-Ay. Just plain irritating.

Like any decent comedy programme The Banana Splits had their catchphrases and regular routines such ‘Hey Drooper, Take out the trash….’ Drooper was the most laid back of The Splits. One could have imagined him puffing on a J (if we’d known what that was in those days) behind the backlot between scenes. Fleegle would encounter all sorts of difficulties collecting the mail each week. Every week. They would also have to try and translate Snorky’s toots and honks each episode.

Interspersed between the Splits‘ ‘crazy’ antics were a few cartoon and live action serials. One-trick pony cartoon Arabian Nights (Size of a cow!), a cartoon version of that most overdone novel The Three Musketeers and the mildly racist live action Danger (Uh-oh, Chungo!) Island. I don’t remember any of my pals being fans of The Banana Splits exactly but we watched it every week and it was slightly upmarket of any offering from The Children’s Film Foundation.

Due to his fame on Pufnstuf and the Kroffts’ involvement, Jack made an appearance on The Banana Splits Show, an event he remembers very little about as he wasn’t really aware of how big they were at the time. All he remembers about it was that he entered The Banana Splits‘ house sliding down a chute, which sounds about right. He bought an expensive camera with his appearance fee.

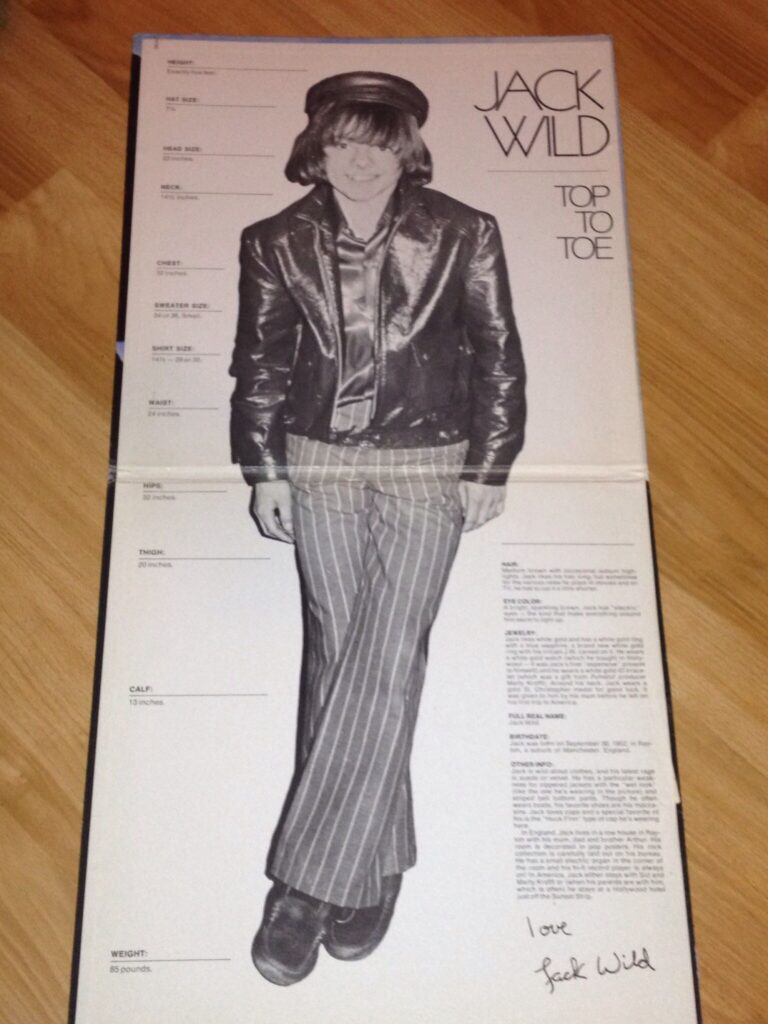

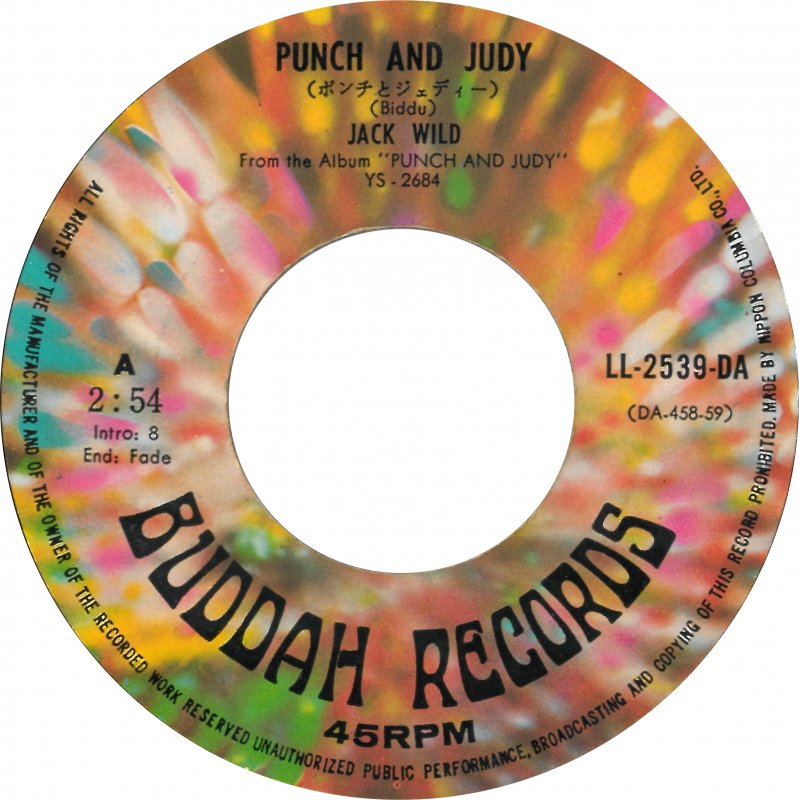

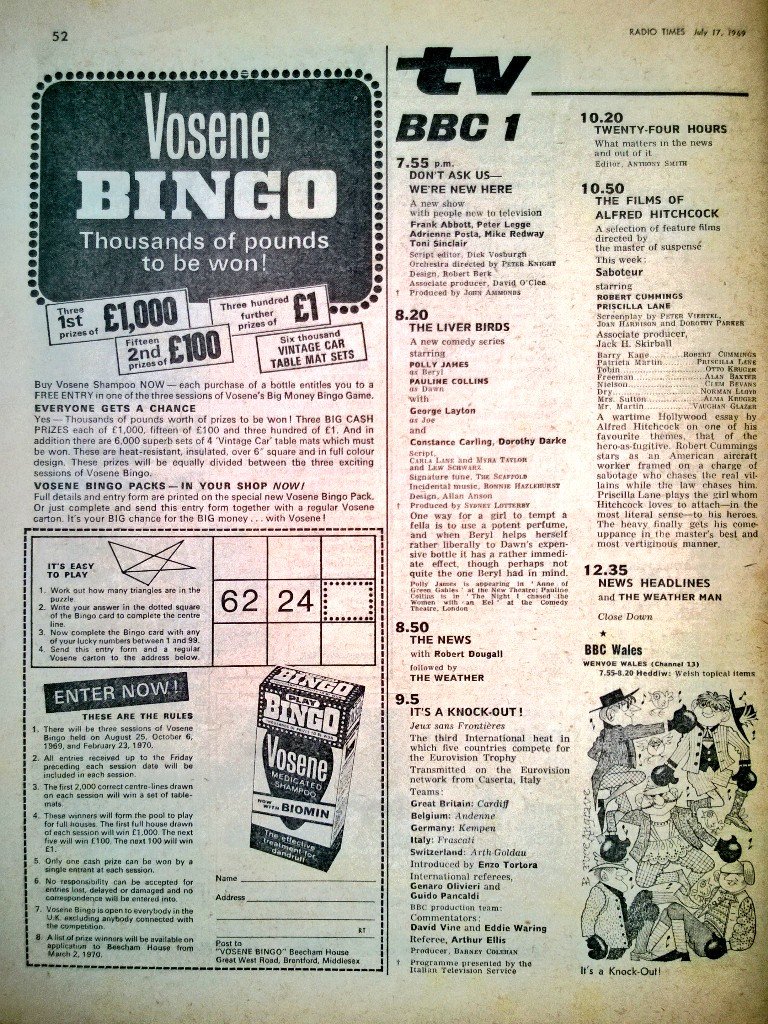

It’s difficult to imagine just how famous Jack was during the early 70s, particularly in the US. It’s always an indication of someone’s popularity when some record producers see the chance of making a fast buck by cashing into this fame. And such was the case with Jack Wild who released three albums of mainly cover songs: The Jack Wild Album, Everything Comes Up Roses and Beautiful World. He even appeared on Top Of The Pops on 6 July 1970 singing his current single, Some Beautiful, which only reached a high of 46 despite heavy airplay on Radio Luxembourg. Interestingly his TOTP appearance created some short-lived tabloid controversy (is there any other kind?) when the producer dropped unfashionable warbling diva Dorothy Squires, of all people, for Jack. As you can imagine, The Squiresatollah was less than happy and kicked up an almighty stink. Sadly, even this gilt-edged publicity didn’t get Jack any higher in the charts. The show itself was an interesting one, as so many TOTP’s from that era were, and was introduced by friend of The Royals and Margaret Thatcher, a certain Jimmy Savile. The line-up ranged from heavy duty MOR to psychedelia and R-A-W-K and was as follows, with chart standings, and, no, I’ve no idea who Soft Pedalling were :

(1) MUNGO JERRY – In The Summertime (and chart rundown)

(21) HOTLEGS – Neanderthal Man

(2) FREE – All Right Now

(NEW) JACK WILD – Some Beautiful

(10) SHIRLEY BASSEY – Something

(NEW) SOFT PEDALLING – It’s So Nice

(28) JONI MITCHELL – Big Yellow Taxi (video)

(NEW) DOZY, BEAKY, MICK & TICH – Mr. President

(20) TEN YEARS AFTER – Love Like A Man (video) (danced to by Pan’s People)

(NEW) COUNTRY JOE MacDONALD – I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ To Die Rag

(13) ELVIS PRESLEY – The Wonder Of You (video)

(4) THE KINKS – Lola (crowd dancing)

(1) MUNGO JERRY – In The Summertime

As well as an appearance on TOTP, he notched up 7 (seven) appearances on Genxculture favourite, Lift Off with Ayshea including a ‘Jack Wild Special‘ on 3 November 1971.

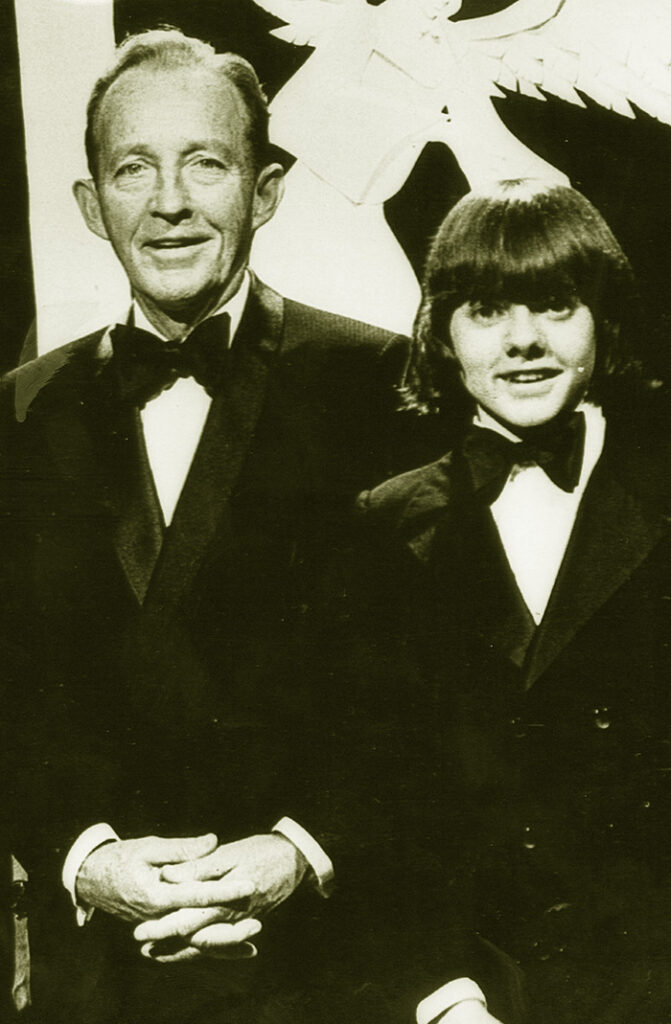

His singing career in the US led to hysteria when he made personal appearances at record stores (as they call them) and chat shows all over the country! It was around this time that Jack was also asked to appear on The Bing Crosby Christmas Special. He was also invited to perform his new single on The Johnny Carson Show, America’s most watched chat show. Having completed three films and a hugely successful US TV series, Jack was becoming something of a diva. He admits this in his autobiography, ‘It’s Dodger’s Life‘, published shortly before his untimely death in 2006. At the age of 16 he’d already sacked his agent, June Collins, and various other ‘mentors’ in his life and decided he didn’t want to sing on Johnny Carson as his musical director wasn’t available, so he turned it down. A quite mind-boggling decision for a 17 year old.

He was also asked to introduce the great Tiny ‘Tiptoe Through The Tulips‘ Tim (See The Utterly Weird Adventures Of Tiny Tim), a Rowan and Martin Laugh-In regular, at LA’s legendary Troubador club. This also almost went tits up as Jack discovered TT was wearing the same shirt as he was and he nearly pulled out of the introduction when he was asked to change. He did go through with it but was less than happy. He expected Tiny Tim to change rather than him, which wasn’t going to happen. That said, Jack felt TT was ‘completely out of it‘ (although this was how TT usually came across to people) anyway and totally oblivious to the shirt faux pas.

This was a measure of Jack’s fame in the early 70s that he had the power at such a young age to make almost career-changing decisions and it was also the time when alcohol began to play a more significant part in his life. No one around him felt influential enough to warn him of the consequences of some of the decisions he was making as they all relied on him for at least part of their livelihood. Such are the vicissitudes of fame.

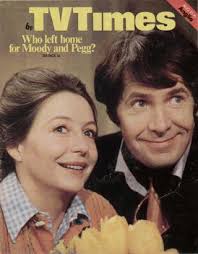

But his life in the early 70s was still a rollercoaster of transatlantic success, and after making the excellent Alan Parker-directed Melody about teenage romance with his old mucker Mark Lester he then teamed up again with his old Oliver! mentor Ron Moody to make the film Flight of the Doves in Ireland. One of the oddest stories from the making of this film was how, according to Jack’s autobiography, he was convinced that his parents were trying to force him and his co-star, Dana (yes, that Dana), together throughout the duration of filming. That would have been a romance made in tabloid heaven. Think he had a lucky escape there….

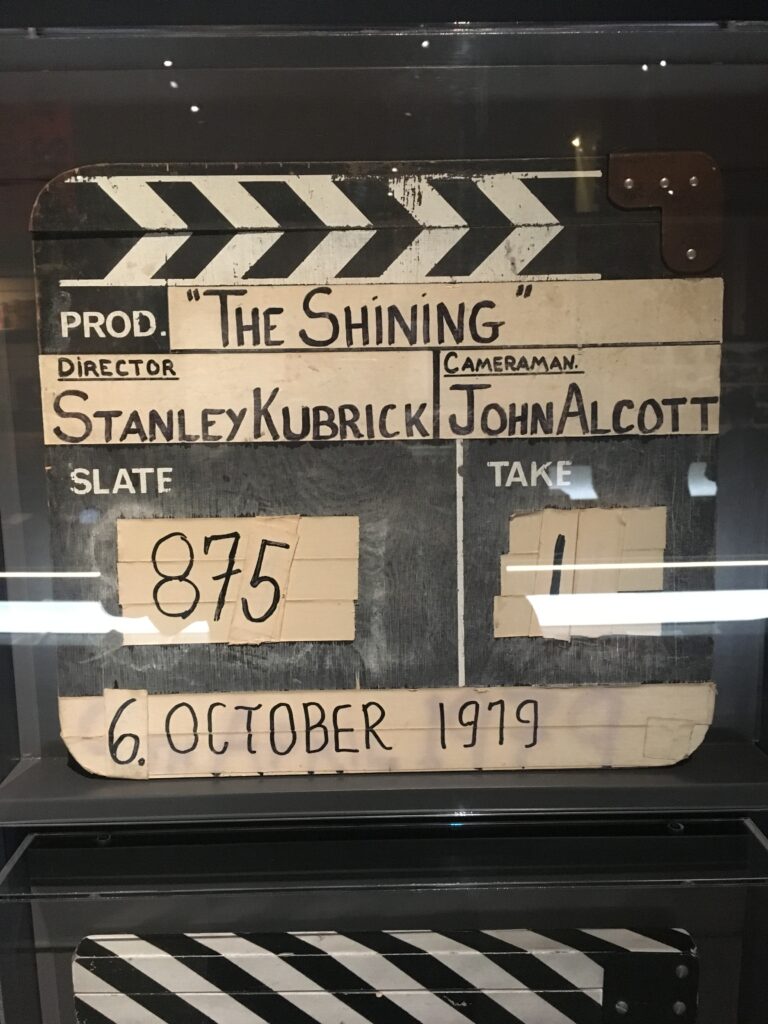

A particularly interesting film he was asked to appear in, although Jack was not particularly enthusiastic about it, was a David Puttnam production of The Pied Piper of Hamelin starring 60s psychedelic troubadour Donovan and directed by French auteur Jacques Demy. An interesting cast included John Hurt, who Wild got on very well with, Michael Hordern, Roy Kinnear (who also appeared with Jack in Melody) and the inevitable Diana Dors. Jack was asked by Donovan, who had written the film’s soundtrack, to sing a song in the film but, again, he refused, as he felt he wasn’t up to singing ballads and was more at home with up-tempo numbers. It was another example of Jack’s burgeoning confidence which may not have gone down too well with directors.

So far so good, but eventually fame begins to thin a little and the public and media find new people to adulate. That’s not to say Jack’s career imploded but the parts he as being offered were becoming less interesting. After his period as the cheeky young chappie everyone loved, he was growing older but casting directors didn’t think of him as an adult. Wild was also aware of this and he was becoming frustrated at the fact he was 18 and still being asked to play schoolkids.

Film roles began to dry up after The Pied Piper. Jack continued to work but in TV series such as The Onedin Line and another Dickens’ part in Our Mutual Friend followed soon after by another classic TV serialisation, Gogol’s The Government Inspector, also featuring ‘Doctor’ Robin Nedwell.

In-between these two fairly prestigious TV productions Jack starred in a film already mentioned elsewhere in this little blog site (see Standing At The Crossroads Of (TV) Quality), a film written by Crossroads‘ creator Hazel Adair, who, in an unlikely collaboration with wrestling commentator Kent Walton, went in for a bit of soft porn in her latter years. Keep It Up Downstairs says pretty much all about the film and Jack’s claim that he had little idea of what it was all about until he viewed the finished product is slightly dubious. But it was an earner when the offers begin to dry up a bit and I’m sure respected actors like the ubiquitous Diana Dors, Willie Rushton and the lovely Aimi MacDonald, who also appeared in the film, were just happy to take the cash, and who can blame them? Even illustrious film composer Michael Nyman provided the soundtrack. Well, everyone has to start somewhere….

It must have been an extremely odd viewing experience to have watched Jack as, ahem, Peregrine Cockshute but at least he was being offered an adult role!

It was around this time that the decent roles really did begin to dry up and his drinking began to take off. In his autobiography It’s A Dodger’s Life, he describes how he made Keep It Up Downstairs almost through the haze of alcohol. He feels he just about got away with it but people in the TV and film industry are not stupid. One can’t help but think that this was noticed and, of course, these stories circulate very quickly. Jack himself tells the story of highly respected actor John Collin, who appeared with him in Our Mutual Friend. It was well-known throughout the production that Collin had a drink problem and all the actors were instructed to do what they could to keep him out of the pub. One can’t help but feel that maybe Jack’s drinking also became known over the years and this, more than anything, could have affected the number of parts he was being offered during the mid to late Seventies.

Around the same time a successful court case brought by June Collins, his first agent, against Jack’s agent of the time, was also a huge setback in his career. The outcome affected Jack in the sense that he picked up the not inconsiderable tab for the case and had to pay June Collins a substantial sum for ‘lost earnings’ despite not really doing anything wrong other than change his agent. It’s true he did become something of a ‘diva,’ which he fully admits, when younger, but this story, once again, highlights the precariousness of showbiz.

During the mid-70s Jack returned to the US to appear in a Krofft brothers production at the Hollywood Bowl and it was here when Marty Krofft suggested to Jack he stay in LA and find work in Hollywood. This was not an unrealistic possibility as Jack was still very well-known in the US and a great favourite of the successful Krofft Brothers. Jack decided against it, however, as all his family were still in the UK but one can’t help but speculate whether his career might have been more lucrative in the US. Of course, drinking may still have been a problem amongst other distractions but maybe if he had been working more regularly he might have kept things more in check? Who knows, but it was a pivotal decision for Jack at a time when his career was certainly hanging in the balance.

During the 80s Jack’s work pretty much dried up. Was this because of his drinking? It was certainly a huge factor. Although a part in Kevin Costner’s blockbuster, Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves looked like Jack might be getting back on the rails, it was too little too late. His health began to deteriorate seriously as did his private life.

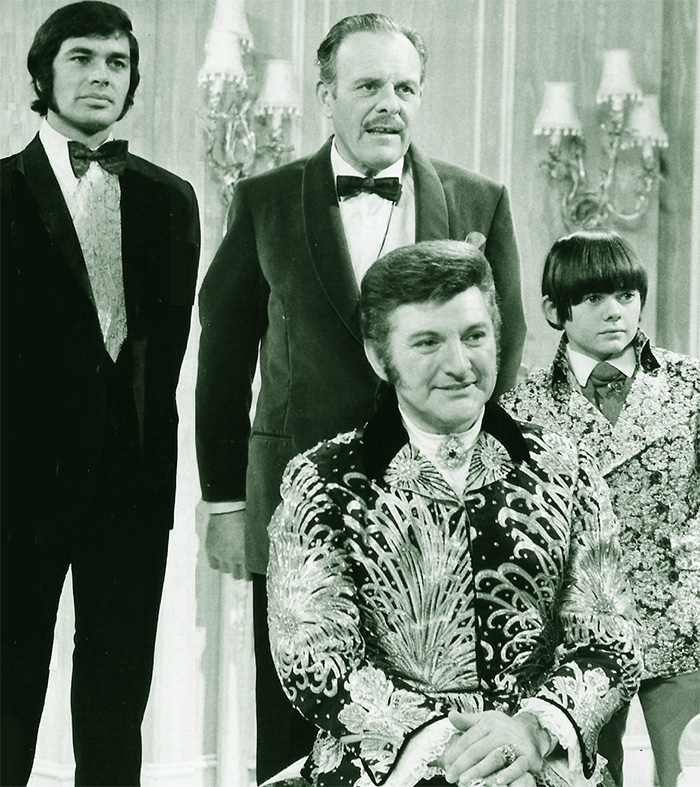

It’s a situation seen too often in the showbiz industry but in his autobiography Jack doesn’t go in for self-pity. He knows he was solely to blame and how it affected not only himself but also the people around him. His story is tragic not just because it wrecked his career and his marriage but also because it denied the viewing public of a unique talent. Everyone knew and loved Jack Wild at one time. He was, without doubt, one of the faces of the seventies and no one of a certain age will forget Oliver! or HR Pufnstuf. He was ubiquitous, appearing on the most watched variety shows in both the UK and the US including The Liberace Show, Bing Crosby Christmas Special, The Englebert Humperdinck Show, The Val Doonican Show, The David Frost Show and that Genxculture favourite, The Golden Shot (Like A Bolt From The Blue..The Golden Shot), amongst many others. And what is just as tragic is to consider what he could have done had his career not been destroyed by booze. He would have been a shoo-in for Eastenders, for example. Sought after for Celebrity Big Brother and I’m A Celebrity, Get Me Out Of Here. OK, these shows are not at the top of the professional ladders but they’d have been good earners for Jack and provided him with a pretty decent lifestyle and kept him in the public eye. Also with the, albeit brief, resurgence of the British film industry in the 80s and 90s driven by David Puttnam and Alan Parker, both of whom Jack worked with, there could have been many opportunities for Jack to become what he really wanted to be, an serious adult actor. And he could have achieved that.

I could also have seen Jack as a lively and entertaining compere in various TV shows similar to the type Ant and Dec front. Britain’s Got Talent would have suited Jack down to the ground!

But it wasn’t to be. Jack Wild died after a long battle with cancer, which he said was the result of his heavy drinking and smoking, in 2006. But he left behind a wonderfully strange and beautiful legacy of work which is still watched and enjoyed today. For a glorious period in the late 60s and early 70s, Jack Wild was the kid who had it all.

![Mr Sardonicus (1961) [31 Days of American Horror Review] – BIG ...](https://www.genxculture.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/image-6.jpeg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-10592291-1501739185-7455.mpo.jpg)