Compared to the games shown on The Big Match, everything about today’s football is better.

Only so much more boring.

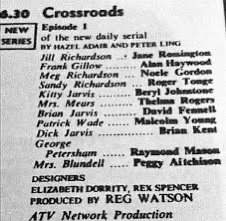

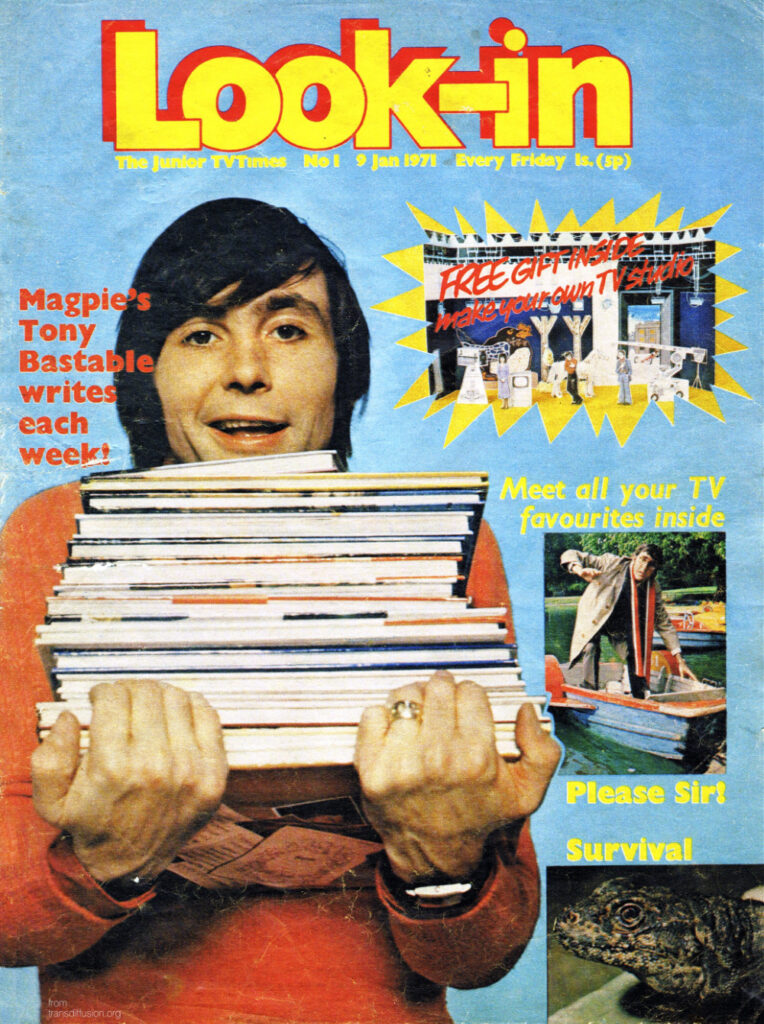

In quiet weeks during the football season the good people at BT Sports often show episodes of that 60s and 70s highlights mainstay The Big Match presented by the legendary Brian Moore. In Scotland we had our own football programme as did every other TV region in the UK, each region showing highlights of their local team’s home fixtures. As well as a Scottish First Division game we also were given highlights of a top English game too. The Big Match, which was broadcast to the London region, featured a London game plus highlights from one or more of the regions, ‘..and today’s pictures are from our friends at Anglia TV,’ Brian would say. Commentators in all the ITV regions were as familiar as the teams themselves. The great Arthur ‘What A Stramash!’ Montford (more on him later), Gerald Sinstadt at Granada, Keith Macklin at Yorkshire (who also hosted a Sunday tea-time religious quiz show and the first series of Pot Black), the illustrious Ken Wolstenholm at Tyne Tees and Hugh Johns at ATV. We all knew these guys’ voices, certainly more so than the competent but anonymous commentators of today.

And who could forget Idwal Robling? Although a BBC commentator, he entered a competition in 1970 to win a place on the BBC commentating team for the 1970 World Cup. He fought off challenges from Ian St. John, Gerry Harrison and Ed ‘Stewpot’ Stewart (funny how he turns up so often in this blog) to clinch the job, after Alf Ramsay (who reportedly had a love of the Welsh accent) gave him the nod when he tied with St. John. Sadly he didn’t get a live a gig at the World Cup but did some first round highlights games.

Although the football could be pretty humdrum in these programmes, so much about how football was televised, watched, discussed and presented in the 70s continues to be fascinating, given the way the game has changed over the last 50 years. Like anything, sometimes for the better but frequently for the worse.

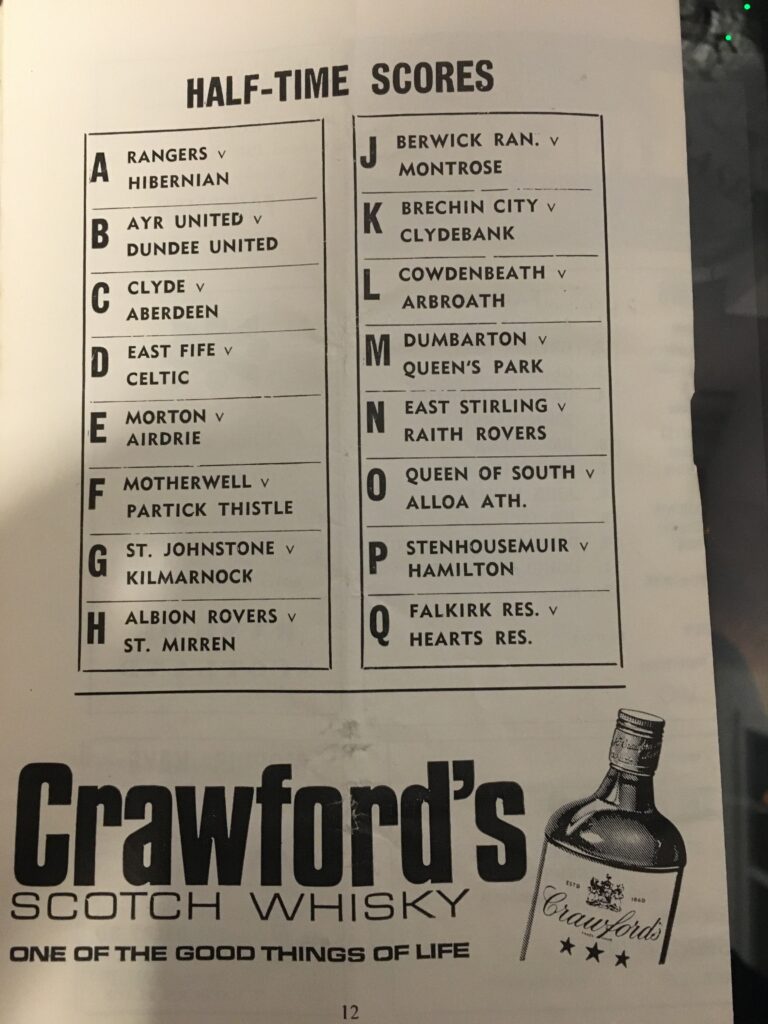

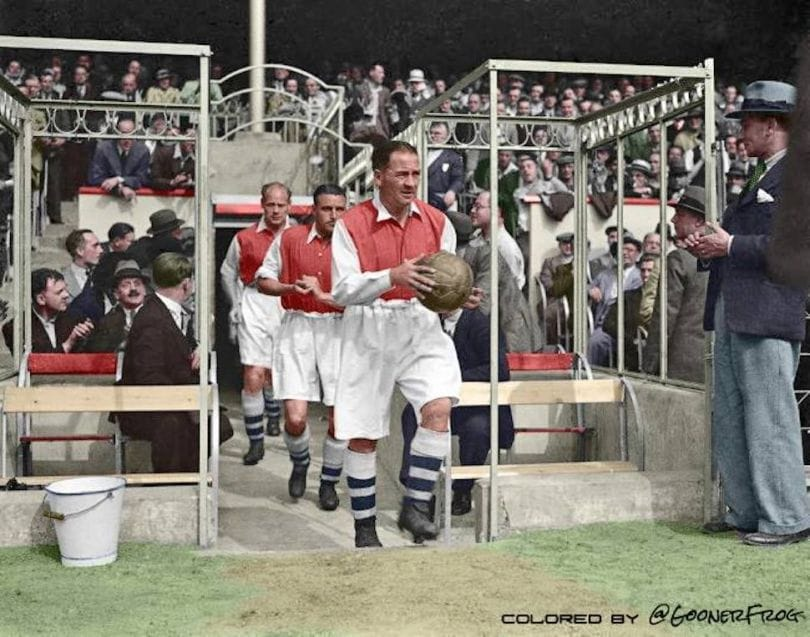

It’s fair to say the 60s and 70s were a more innocent time for football. Relatively few games were broadcast, from a fixture programme of about nearly 150 games, maybe 20-25 might have had highlights featured around the country. 24/7 satellite and cable football coverage was a long, long way off and, because of this, you appreciated football on telly much more. Live games were very rare and tended to only be the Scottish and English cup finals, a few Home Internationals and World Cup games every four years. The idea of billions being pumped into football was just a pipe dream.

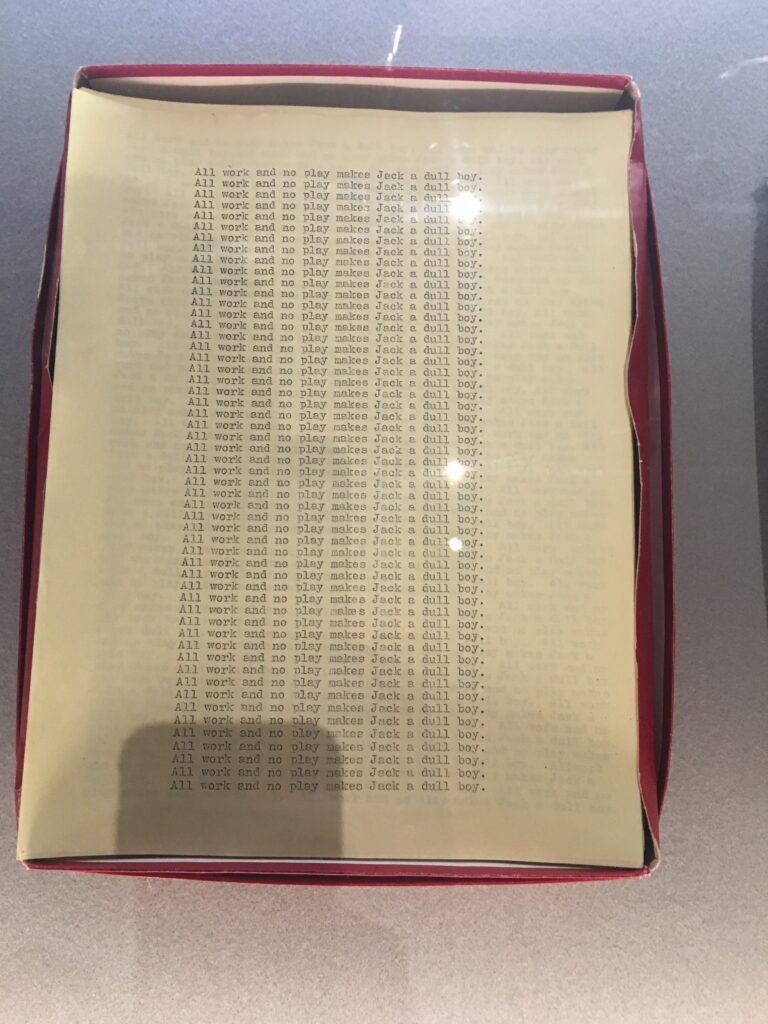

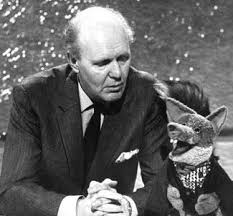

And talking of pipes, the legendary Brian Moore presented The Big Match and commentated on the featured games between 1968 and 1983 and his pipe was never far away. Lying stationary on his otherwise empty presenting desk or in a small ash tray, in later years it disappeared, clearly because producers thought 9 year olds watching the programme on a Sunday might begin puffing on a Churchwarden and using their pocket money to purchase half an ounce of rough shag in the local tobacconist. Brian Moore was The Big Match, he was to ITV what David Coleman was to the BBC, the voice of football.

Brian had a child-like love of football. He never really stopped seeing it the way a 14 year old sees it. As a heroic, tribal, virtuous endeavour where cynicism was a word footballers didn’t understand. Well, that was probably true, but not in the innocent way Brian thought. In fact, the opening credits to the programme, which changed every so often, always featured a few ‘wacky’ incidents and characters, which was in keeping with Brian’s rather sanitised and rosy view of the game. As The Big Match also included an awkward interview with a hirsute, wide-lapelled player or manager who had been involved in the televised game, Brian’s awe and excitement was often palpable. Difficult questions were rarely on the agenda, although the inarticulacy of the player often found any question difficult.

While commentating on a game Brian was always trying to find the best in players. If something mildly amusing happened like a player helping one of the opposition to his feet after a hefty tackle, Brian would begin to chortle and say ‘That’s lovely to see!’ He so desperately wanted to see the ‘nice’ side of the game. Barry Davies on the BBC was similar in his adolescent adulation of professional footballers. In interviews he would always chuck them questions in the hope of getting a marginally droll response. Commentators like Brian and Barry just loved Ron Atkinson, for example, or ‘Big Atko‘ as the Saint and Greavsie chummily referred to him (footballers and managers’ nicknames always had to end in ‘o’ or ‘ie’). In an interview before Ron Atkinson’s West Bromwich Albion had a big cup game against Ipswich Town, Barry Davies took him around Wembley Stadium followed by the BBC cameras obviously, and led him into the home dressing rooms. They were empty but for an Ipswich Town shirt which, coincidently, had been left hanging there (by a BBC production assistant, no doubt). ‘Oh look!’ grinned Barry and beamed as Ron spotted this shirt and lifted it off the peg. He was almost pissing himself in anticipation as he awaited Atko’s inevitable side-splitting bon mot. Which never came. He just stood there examining it, mumbling ‘Hmmm, yeah…’, desperately trying to think of something amusing or even faintly interesting to say. Poor Barrie. What a blow. And this, I think sums up commentators’ interactions with many footballers. To use one of their favourite words, disappointing.

And it’s not just limited to footballers. Often The Big Match would involve celebrities in their Christmas Special shows and in 1976 presenting duties were handed over to none other than Chairman of Watford FC, Mr Elton John. To describe Elt as wooden at the start of the show is an insult to wood and maybe the producers were a bit worried about this so they wheeled in two ‘jack- the- lads’ of the game, Mike Channon and Kevin Keegan to lighten up proceedings. They began the show wearing flamboyant glasses and earrings. Oh, you boys…! The banter began to dry up a bit after this, a bit like their England careers at the time, but not before The Big Match annual Christmas ‘bit of fun’. This involved clips of games, players, referees from over the year being speeded up, reversed, repeated etc. And, no, it’s not nearly as funny as it sounds (and it doesn’t sound nearly funny really). ‘That’s the best one ever‘ exclaims a tittering Elton.

I know it’s easy to mock and technology was much less sophisticated then, and they really weren’t very funny. But who cared? It was what it was at the time. And despite Channon and Keegan firing comedy blanks, can you imagine Kevin De Bruyne or Harry Kane (I’m actually struggling to think of any other International players, such is most modern players’ lack of personality) going on to some football programme today and hamming it up?

There are many things you notice about these 70s highlights programmes that are so different to today’s clinical, over-technical, often skilled but tedious fare we are served up.

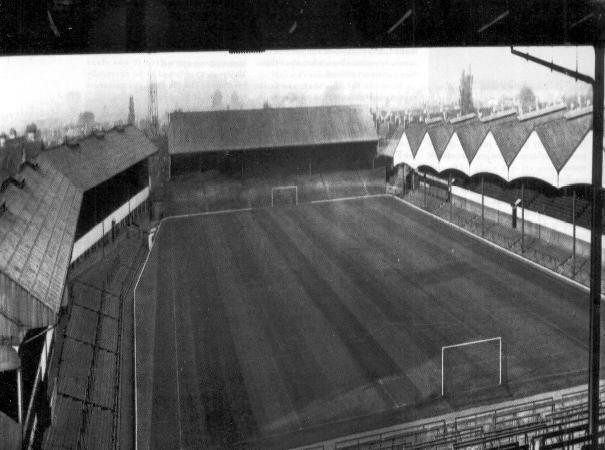

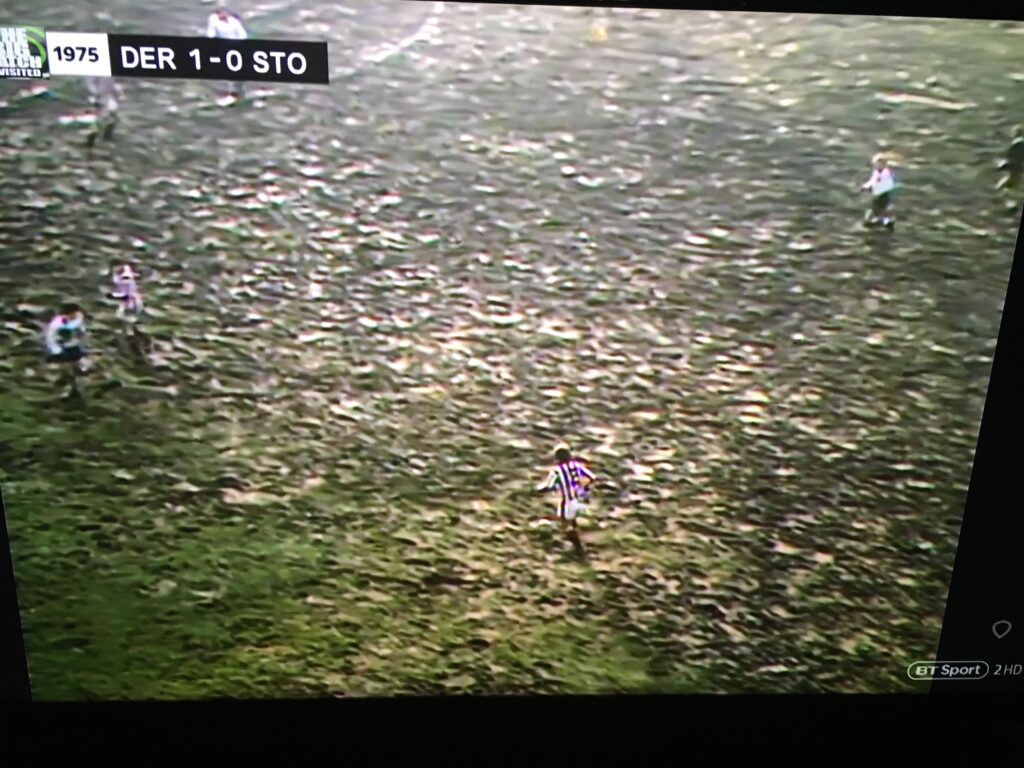

The pitches for one thing. By October every ground featured was at best a mud-bath, at worst a ploughed field. But, strangely, this didn’t detract from the games, it actually enhanced them. Players had to dig in, sometimes literally, and the skill of many to negotiate these quagmires was impressive. Sometimes it was difficult to know what the ball was going to do and this ramped up the excitement. Some pitches were notorious, and not just in the depths of winter. You’d have done well to spot a blade of grass on Derby County‘s Baseball Ground at any time of year, for example. And despite all their loot, Old Trafford was pretty awful. In fact, it’s easier to try and think of a ground where the pitch actually held up reasonably well during the middle of the season. And the amazing thing was, all the commentators would concede was ‘..conditions underfoot were tricky.’

At the end of games it was customary for young fans, usually in parkas, to run on to the pitch and mob their heroes, whether they won or lost. Police didn’t seem that bothered and the commentators didn’t even refer to it. Someone ‘invading‘, as it was described at the time, was a fairly common occurrence then and occasionally, however, some bozo would run on to the pitch during a game. Usually the guy was completely stoatious and it was generally good-humoured, it even added a bit of levity to a very dull game. Particularly when he evaded the rugby tackles of pursuing coppers. On highlights programmes like The Big Match the cameras would actually follow the invader around the pitch and even have a laugh about it. In the rare event of it happening now the sniffy commentators would just say ‘We don’t want to see that.‘ In fact, we do! It would be a welcome break from the tedium of watching Manchester City or Chelsea or Spurs pass the ball back and forward in their own half for 10 minutes. Now seeing them try to perform that at The Baseball Ground would have been interesting. But like so many other common elements to the 60s and 70s game, pitch invasions are a thing of the past. My favourite pitch invasion ever was after the legendary Ronnie Radford scored that screamer for Hereford United against Newcastle United in an FA cup tie in 1971. Never have so many parkas been concentrated in one relatively small area.

Occasionally The Big Match cameras might go ‘behind the scenes’ after a match, and such was the case after the Southampton v Manchester United clash in 1973. Brian couldn’t hide his excitement when he announced that TBM had been kindly invited into the players’ lounge after the game. A fairly lengthy item followed where a grinning Brian followed players of both teams around the rather cramped, formica-lined environment with a microphone. What made this particularly interesting watching it now was that every player interviewed was knocking back a pint. And, of course, no viewer then would even have remarked on it. And why would they? It’s only in recent years that footballers, some at least, are described as ‘athletes’, non-drinking and only eating a macro-biotic diet (whatever that is). I don’t think Frank Worthington, Stan Bowles or Rodney Marsh, great footballers that they were, would have any truck with this type of lifestyle. It’s rumoured that Frank Worthington failed a medical in the 70s to sign for Liverpool due high blood pressure brought on by ‘excessive sexual activity.’ ‘They were great days,’ said Frank. He was probably also referring to his football career.

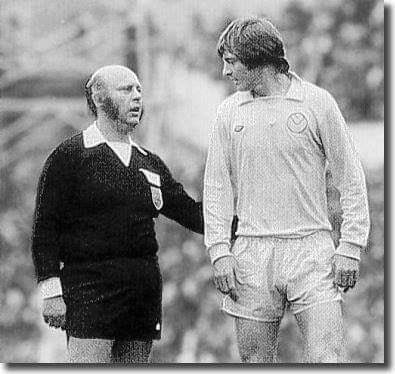

The approach of referees to the vicissitudes of the game was also very different. Referees tended to be elderly, portly gentlemen who held down responsible jobs during the week, such as a Shipping Clerk or Woodwork Teacher. Players rarely questioned his decision other than a childish moan and a group of players surrounding a referee was unheard of. It took a lot to be booked in the 60s and 70s and even more to be sent off. Scything tackles were common but only occasionally punished and the term ‘professional foul’ was not in the vocabulary. A word in the ear was all that was usually needed. And referees universally wore black, in fact one of the more expressive chants from the terraces of the time, ‘Who’s the bastard in the black?’, has been rendered virtually meaningless thanks to the modern referees’ rapidly expanding palette of flamboyant bright colours.

Which brings me to another ‘Grumpy Old Man’ point. How irritating is it when a commentator apologises for any ‘bad language’ that may have been heard while a live game is being broadcast? Is there anyone in the world watching live games who isn’t aware of the type of language that tends to be heard at football? Is there any football fan who might be shocked or offended by that type of language? Is there anyone who even notices it when it’s broadcast? Brian certainly never ever referred to it. But he probably thought all football fans were of the type that featured in Roy of the Rovers comic strips. Bless him!

Another regular feature of The Big Match was viewers’ letters. Two or three letters were usually read out by Brian, most of them from teenage fans. What I particularly liked about this item was the fact that Brian used to read out their full address on the programme. For what now takes a matter of seconds, a correspondent would have to find a postcard (not particularly easy), write his (and it was usually a ‘him’) question or request, buy a stamp, take it to a letterbox and post it, probably wait 2-3 weeks in the hope that it might be selected for broadcast. What a palaver! A bit like voting for acts on Opportunity Knocks! For example, on the 8th September 1974 edition 13 year old Tony Woodward of 45 Blossom Square, Reading in Berkshire wanted to know why Keith Peacock, playing for Charlton in the previous week’s televised game versus Gillingham, changed his shirt at half time? You can’t pull the wool over the eyes of some eagle-eyed young fans! And Brian revealed that Keith perspires a great deal and so changed his shirt at half time, so there you have it Tony. You’ll have slept soundly that night having had your burning question answered and you now know it’s because Keith Peacock is a sweaty bastard. On the same show 14 year old Steven Brill of 31 Seddington Road, Hendon wanted to know if it’s legal for goalkeepers to swing on their crossbars. The short answer was yes and no. Hope that answers your query, Steve. Keep those letters coming.

Talking of this 8th September 1974 edition, it featured a match which summed up the vagaries of league football as it was a second division game between Fulham and York City which the visitors won 2-0. A couple of interesting points from this game (and there are always interesting points I would argue). York City were then in the second highest tier of English football, they now occupy the National League (North) and play the likes of Spennymoor United, Farsley Celtic and Alfreton Town. Their strip was maroon with a distinctive white ‘Y’ motif which looked like they had been sewn on individually by the manager’s wife. And the York City manager Don Johnson (no relation I believe) puffed away on a pipe in the YCFC dugout throughout the game.

Playing for Fulham were Bobby Moore (who looked well past his sell-by date, looking slow and overweight) and Alan Mullery, who joined Brian in The Big Match studio on the Sunday afternoon to discuss the game. Fulham were managed by tweed-wearing, pipe-puffing Alec Stock, an old school campaigner and a dying breed even then. Paul Whitehouse claims to have based Ron Manager on him and in an edition a few weeks later Stock was interviewed in the TBM studio after a game against Southampton and he railed, gently, against the ‘Southampton chaps‘ who had been a little overzealous in their tackling. Marvellous.

Ron Manager

Alec Stock

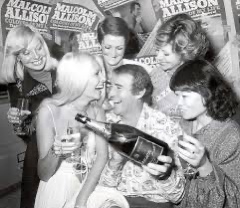

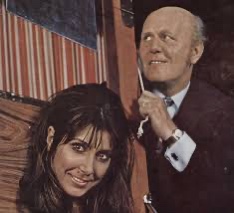

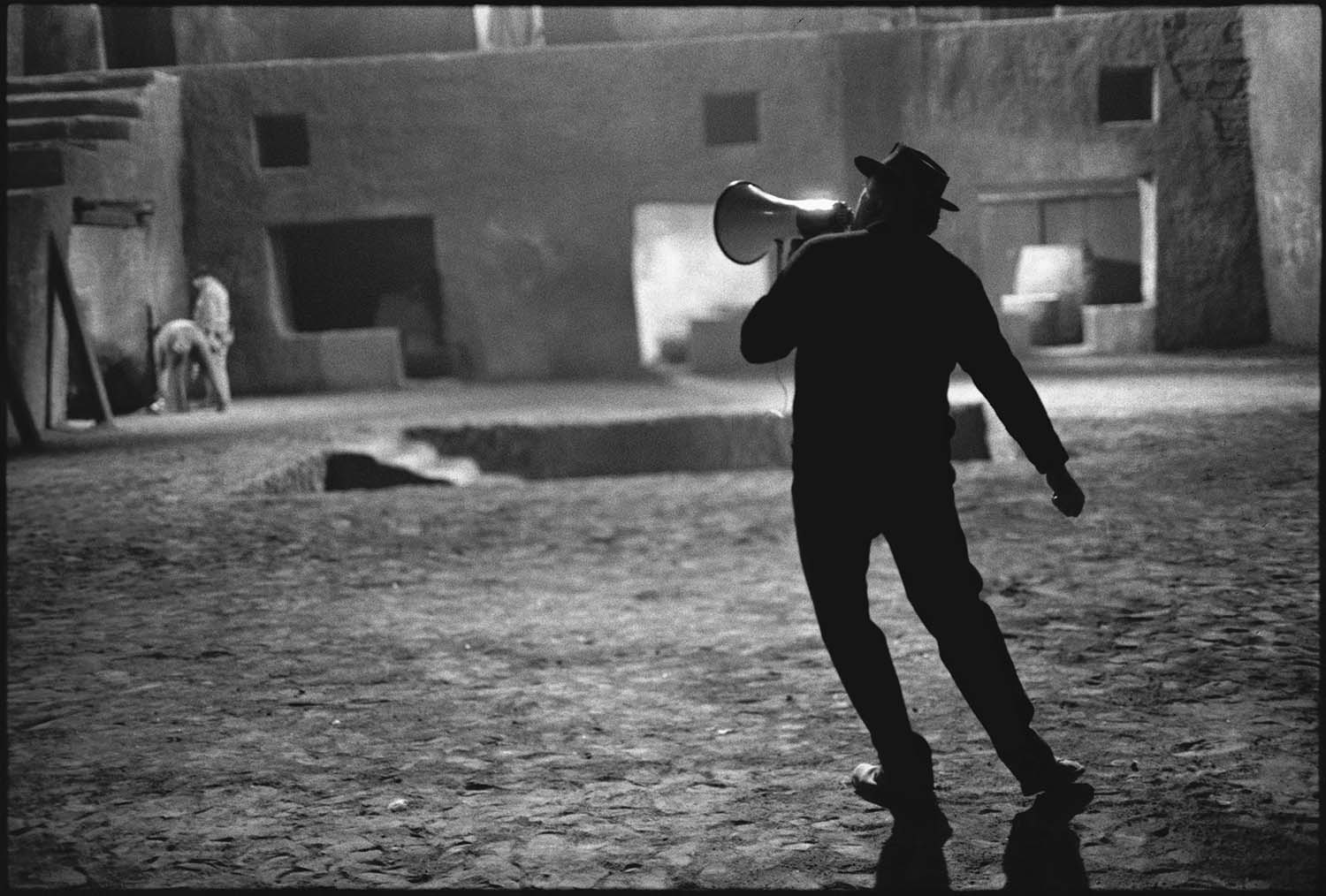

It’s fair to say managers (and they were mostly managers, not coaches at this time) were a very different breed. Pipes were almost de rigeur as the manager, trainer and sub huddled in the cramped, wind blown dugout during the game with only a tartan rug covering their knees. There was none of this prowling around the technical area, dementedly pointing and waving, bellowing at the fourth official or booting bottles of water around if the decision went against you. Although during the mid-70s the egotist manager did begin tentatively to emerge. And who was the first such individual to see himself as a ‘personality’? Step forward Malcolm ‘Big Mal’ Allison, Crystal Palace ‘coach’ and friend of Brian Moore.

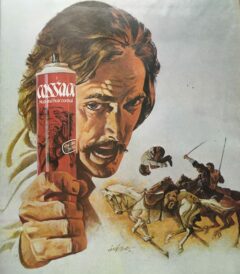

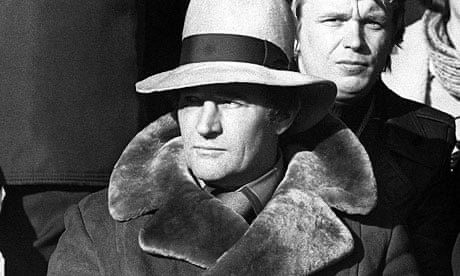

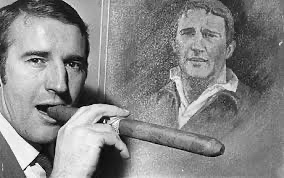

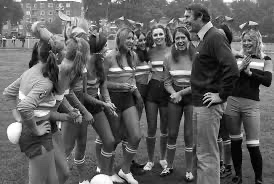

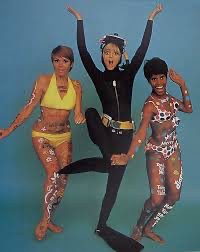

Malcolm Allison had been at Manchester City before landing the ‘glamour’ job at Crystal Palace. His Man City track suit was binned and replaced with a fedora, an oversize sheepskin coat and an enormous Cuban cigar. The personality coach had arrived! Malcolm milked the flashy side of coaching to the limit and, in cahoots with the tabloid press, created an image for himself that still endures. In fact, the flick-to-kick football game Subbuteo included a model of a fedora and sheepskin- wearing manager to stand on the sidelines looking not dissimilar to Big Mal in his heyday. One of his most memorable stunts was to invite Playboy columnist and glamour model Fiona Richmond into the Palace communal bath, and, as they frolicked in the bubbles, a tabloid photographer snapped away. Somehow you couldn’t imagine Alec Stock doing this. Marvellous as it may have been.

Some years ago I was changing trains at York Station en route to Edinburgh and as I disembarked a large man in a camel coat and an even larger glass of whisky, which had been filched out of the buffet, was waiting to board. It was unmistakably Big Mal.

And talking about Crystal Palace and 70s managers, I recently watched a very interesting BT Sport documentary about the post-Busby Manchester United. Tommy Docherty was interviewed about how he became Man United manager in 1972. He was Scotland manager at the time and was at the Crystal Palace v Manchester United game at Selhurst Park. United had just been humped 5-1 by a Palace team languishing at the bottom of the English First Division. At the end of the game Docherty was invited into the Palace board room by Busby and offered the job on the spot on a 3 year contract at £30,000 per year. That is….£30, 000 a year! I have to say I was quite shocked at this revelation. Manchester United were one of the biggest clubs in Europe and this is what they paid their manager. Today that would translate to just under £400,000 which was, and still is, a lot of money but compare it to what managers/ coaches are paid now and it’s a drop in the ocean.

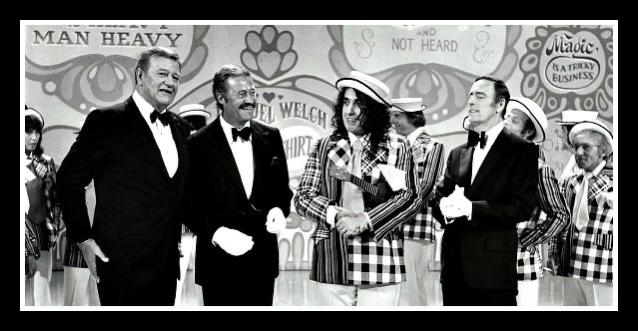

A few years before this edition of TBM, 1970 to be precise, Brian Moore and his colleagues at ITV had opened the television Pandora’s box and unleashed on an unsuspecting TV football audience ‘the pundit.’ In fact it was many, many years before this word would ever be used to describe an ex-pro who talked incessantly and lugubriously about some dull, ultra-fine point he noticed in a boring, meaningless televised game. For the 1970 World Cup in Brazil someone had the bright idea of putting together a panel of ‘experts’ to argue, bicker and nitpick about every World Cup game televised for the whole of July. The first panel comprised Jimmy Hill (inevitable), Malcolm Allison, Pat Crerand (recently retired, ex-Man United and Scotland midfielder), Derek Dougan (talismanic Irish Wolves striker) and Bob McNab (Arsenal full-back). Latterly Cloughie (another of Brian’s muckers and then Derby County manager) and Jack Charlton became involved. Bizarrely, it was one of the few occasions ITV beat BBC football coverage in the ratings, forcing the Beeb to quickly put their own panel together. Football would never be the same. Sadly.

But in their favour, they didn’t use diagrams to show where a striker should have been running, how much space a defender gave an attacker or even mentioned diamond formations. They just squabbled and you sort of knew after the show they’d go out and have a skinful (there were some big drinkers on that panel). And all the time Brian Moore grinned knowing this was pretty innovative telly. He wasn’t to know punditry would eventually disappear up its own back four.

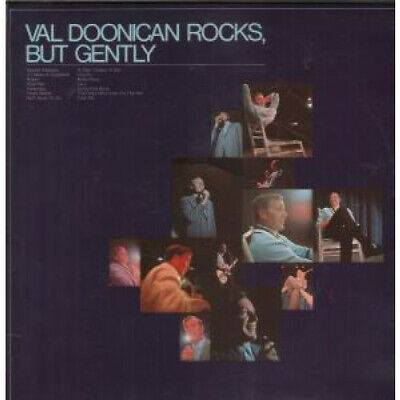

During his long tenure with The Big Match and ITV sport, Brian Moore became a cult figure and a Gillingham FC director. The Gillingham FC fanzine during the 80s and 90s was entitled ‘Brian Moore’s Head Looks Uncannily Like London Planetarium, which was a line from Half Man, Half Biscuit’s track ‘Dickie Davies’s Eyes.’ He died in 2001 aged 69 and it’s fair to say, for the huge football fan that he was, he lived the dream.

The Big Match, and all the regional versions of it, showed players who are now considered greats in action, at a time when football coverage was extremely limited compared to what we have today. And because of that, footage of these players and teams is hugely valuable. At a time when football has become so clinical, so technical and so lacking in real personalities, The Big Match Revisited programmes are an antidote to the tedium which encapsulates so much of the modern game, when a football highlights programme was a part of the weekend you looked forward to and all the better for being rationed. And it’s hats off to Brian Moore for being such an integral and vital part of that experience.

And that was lovely to see.