The long-running show that hit (and sometimes missed) its target

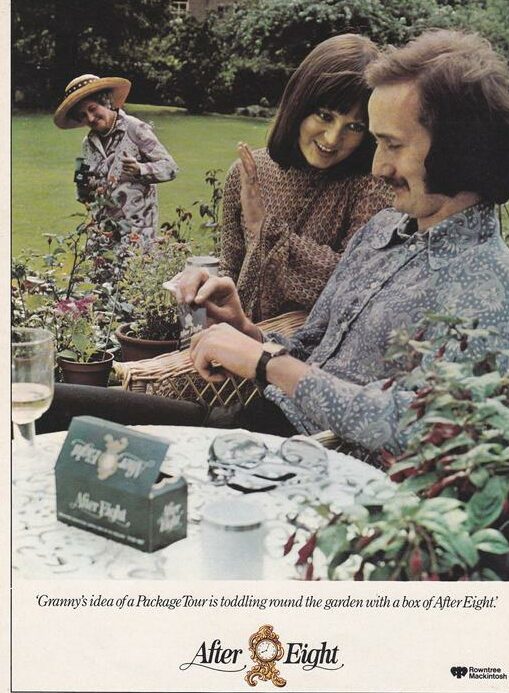

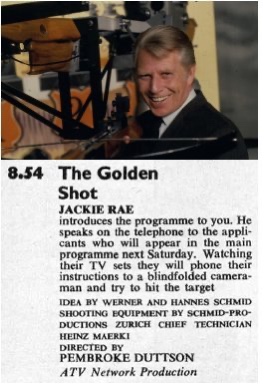

The Golden Shot hit our screens on the 1st July 1967 at 8.54. A curious time for a, then, curious programme, a programme that was rarely off the telly for the next eight years. Based on a German show Der Goldener Schuss, it was one of the first shows (I refuse to use that irritating Americanism ‘gameshow’) to use state of the art technology to help people win prizes. And they were cash prizes worth winning, the ultimate winner having the opportunity to compete for £1000 guineas! Yes, guineas, that quaint denomination used right up to the end of the 70s in an attempt to give certain TV shows a bit of ‘class’. It made the prize seem slightly less vulgar, even for ITV. Competitors had to use various types of machine which hurled projectiles at scenery, the aim being to progress to the next round by puncturing apples. But enough of the format, anyone reading this will know all about that. What’s much more interesting is how this show evolved over its eight year run.

I remember watching the very first Golden Shot, and even at the tender age of 7 being aware that this show was very pedestrian and lacked energy (though I wouldn’t have expressed this observation in exactly those terms). The host was Canadian singer and TV host, Jackie Rae. An affable enough guy, he seemed like the moose caught in the crosshairs. Not an ideal look with all these weapons around. Jackie had been spotted playing a quiz show host on the Charlie Drake Show by the producer, missing the point that playing a quiz show host is very different to being one. In Jackie’s defence, however, he was far from being the worst host The Golden Shot ever had. One critic described TGS as ‘..the deadest, dead duck ever.’ How wrong he was.

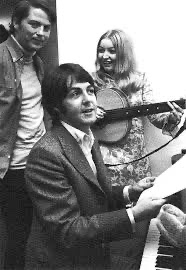

And talking of Golden Shot hosts, The £1000 guinea winner was always Mr Bob Monkhouse. After appearing as a guest on an early show Monkhouse decided it was the perfect vehicle for his unique brand of quick-fire showbiz repartee and by episode 15 poor old Jackie Rae was fired(ho ho). Monkhouse took the whole show under his wing to the extent that he even designed some of the backdrops. His extraordinary ability to ‘fill’ during the many instances of technical breakdown (this was a live show) was invaluable and the awkward longueurs during the Jackie Rae regime were no more. Being paid a mammoth (for the time) £750 per episode, Bob had hit the bullseye!

The above episode demonstrates clearly what an absolute pro Monkhouse was showing the imperturbable qualities required to host a live show where so much can go wrong. No one ever came close to his mastery. And how quaint is it that the contestants are all referred to as Mr and Mrs!

As with everything 60s and 70s, the show had to have a catchphrase and Bob was only too happy to oblige. At the start of every firing attempt by a contestant, health and safety (or what constituted health and safety in those days. See bullet-catching man, below) required the host to ask the crossbow to be loaded. A supernumeracy would then load the dart, or bolt. During Jackie Rae‘s tenure he would say ‘Heinz the bolt!’, he being the inventor of the game. Bob decided this should be more snappy and alliterative and despite strong votes for ‘Basil’ and ‘Bartholemew’, ‘Bernie’ was eventually chosen and ‘Bernie the Bolt’ became the show’s iconic catchphrase, remembered to this day.

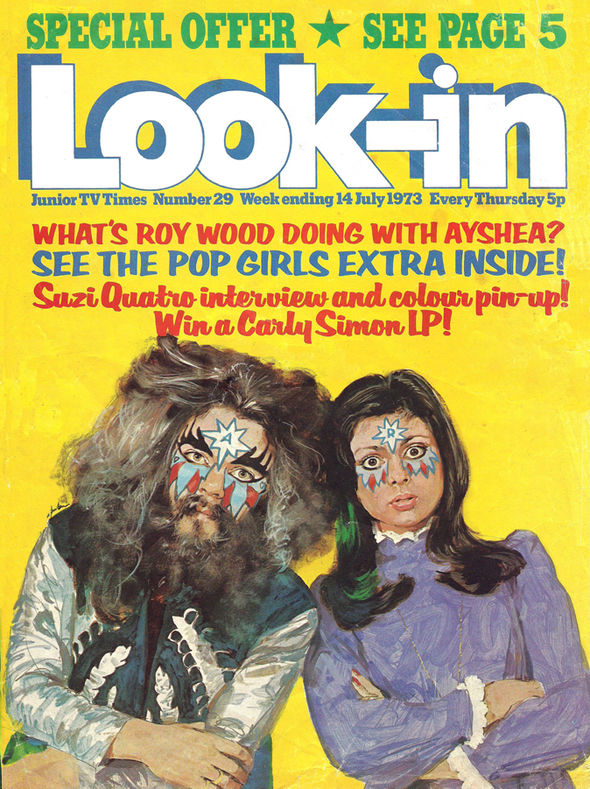

The show introduced us to a few 70s iconographic elements but the most enduring of those was The Golden Girls! Even spawning a long-running (unrelated) US comedy show. The original Golden Girls were tall, blond and dressed arse to tit in gold. Gold lame that is. Two of the originals didn’t last long due to personality bypasses, the only original with any longevity, and of any interest, was Carol Dilworth.

Carol’s 60s and 70s credentials are cast iron. The lovely Carol was a Golden Girl for 91 episodes beginning in the very first show in 1967 and continuing right up to 1969. Of course, Carol really wanted to be an actress and despite appearing in Cliff Richard vehicle The Young Ones in 1961 as a character-stretching ‘Teenage Girl’ and a one-line role in Hammer House of Horror, the roar of the greasepaint and the smell of the crowd was not be. A brief flurry of activity as ‘Girl with dog‘ in Randall and Hopkirk (Deceased), a blink-and-you’ll-miss-her appearance in iconic 70s mega series Budgie (See Budgie: A Monumental 70s Series ), led to Carol returning to what she knew best and a short stint as a hostess in Sale of the Century beckoned. But we hadn’t heard the last of Carol! She married Tremeloes‘ guitarist Chip Hawkes in a 60s marriage made in tabloid heaven. A few years later and they produce 80s icon, the one and only Chesney Hawkes. The Young Ones, The Golden Shot, The Tremeloes, Budgie, Randall and Hopkirk (Deceased), Sale of the Century, Chesney Hawkes. Not a bad 60s and 70s CV. I may make her the patron saint of this blog. The Joan D’arc, the Boudicca, the Brittania of bargain basement 70s telly! Unless, of course, we come across a more deserving figure….

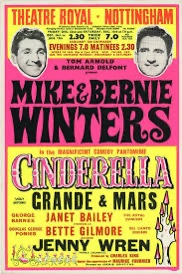

Step forward, Anne Aston! Anne joined TGS in episode one of the second series and clocked up 191 episodes until the very last show in 1975. Anne, or ‘Little Annie’, as Monkhouse unpatronisingly described her, (Golden) shot to fame when it became apparent she couldn’t work out the competitors’ scores and often got them wrong. Whether this was deliberate, as we well know everyone on telly must have their own schtick, or was genuine, it certainly set the women’s movement back 20 years. But, obviously ‘Little Annie’ really wanted to be an actress. Despite landing a starring role in the carry-on style ‘Up The Chastity Belt’ with Frankie Howerd and a small part in Jason King, Annie’s future was not going to be in front of the camera. Coastal summer seasons and pantos beckoned until The Golden Shot was just a distant memory and pocket calculators had become the norm. Not being able to count was no longer cute.

A long-running feature on TGS was ‘Maid of the Month‘. This typically 70s concept was for a current media lovely to be a Golden Girl for a month. Inevitably a glamour model or occasionally an unemployed actress might fill the void. One of those was a blonde Scandinavian actress called Ute Stensgaard. On one show Ute, while introducing competitors, was wearing a garment which was the height of fashion in 1972 (in London, at least). ‘Is that a see-through blouse, Ute?’ asks Bob. ‘Yes it is‘ said Ute. ‘I’ll have to look into that,’ leered Bob. Well, it was the 70s.

A particularly interesting aspect of this period was the range of guests that appeared on variety shows. All shows whether Lulu, Cilla, Cliff, Dusty, Englebert or even TGS had to have guests, if just to give the talent a short break, particularly important on live shows. As there were such demands for guests, and familiar guests at that, sometimes shows struggled to secure the services of Vince Hill, Clodagh Rogers, Dorothy Squires or any other similar ‘C list celeb. Producers had, therefore, to take chances, maybe even experiment. TGS was no exception and as it usually had a seemingly interminable 56 week run, some of the guests who appeared became curiouser and curiouser. One week we had BeBop supremo Dizzy Gillespie and his band playing some avant garde, free-forming jazz. People were astonished at just how much he could inflate his cheeks. A strange brew for Sunday teatime. The legendary Tiny Tim, in one of his rare British TV appearances, also turned up one Sunday afternoon to blow kisses to a bemused TGS studio audience. (See The Utterly Weird Adventures Of Tiny Tim).

But the oddest act ever to grace the ATV studios’ stage featured an elaborate routine which involved a performer who purported to be able to catch a fired bullet between his teeth. Firstly, he chose a, supposed, member of the audience to ‘help’ him with the act. This lucky individual was then instructed to load a rifle, aim and then fire it at the performer’s mouth and he would catch the bullet between his teeth. The tension surrounding this highly stylised act was ramped up courtesy of an increasingly louder drum roll until the gun was fired by the improbably calm ‘member of the studio audience.’ The gun fired, the performer lurched backwards with a Captain Hurricane-like ‘AIIIIEEE’ and, when he’d regained his balance, he removed the slug from between his teeth and dropped it into an awaiting saucer. The audience goes bananas! Amazing! Unbelievable! Not half, as a real gun would have taken the back of his fucking head off and splattered his brains across the Bob Monkhouse-designed studio backdrop. Not to put too fine a point on it. But this is Sunday tea-time and Songs of Praise will be following in half and hour so everything is fine. ‘And that deserves a huge round of applause‘ entreats Bob. Such was 70s variety.

The calmer waters of TGS were thrown into turmoil in 1972, however, when the razor-sharp witted Bob ‘Mr Golden Shot’ Monkhouse was accused by a producer of accepting bribes from Wilkinson Sword, a company who had provided prizes for the show. Bob was summarily sacked and in his last show he made it quite clear he was being made a scapegoat and voiced his displeasure at the producers. In his autobiography written years later it was made clear it had all been a huge misunderstanding and the producers had been wrong to sack him. But, needless to say, Bob had the last laugh.

His replacement, Norman ‘Roses Grow On You‘ Vaughan, had presented the live Sunday Night At The London Palladium (swinging/dodgy) and seemed an, albeit, inferior shoo-in. Monkhouse described him as taking to the show like ‘a cat to water‘ and he wasn’t wrong. Vaughan struggled badly with the quick-fire, quick-thinking format. ‘These are the jokes, folks‘ he’d plead with the taciturn studio audience as the sweat rolled visibly down his powdered forehead. He was released, mercifully, from his contract a year later. He went on to help develop another 70s and 80s iconic quiz show, Bullseye, which was a bit like a pub version of The Golden Shot. It leapt on the popular bandwagon of televised darts in the 70s, but much more on that later. Vaughan’s TV career, however, nosedived.

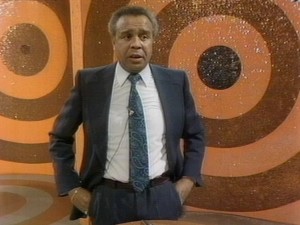

Vaughan’s replacement was the hapless Charlie Williams. A former professional footballer with Doncaster Rovers FC, of Barbadian heritage and graduate of ITV’s deeply suspect The Comedians, Charlie probably couldn’t quite believe he’d been handed one of the biggest jobs on telly. Much respect to TGS producers for giving a black comedian with a thick Yorkshire accent the job, the 70s was hardly a decade of racial harmony, but it was just too much for poor old Charlie. When compared to the ultra slick and professional Bob Monkhouse there was no comparison. Charlie was affable, like Jackie Rae and Norman Vaughan but affability is a one-way corridor and he also couldn’t carry a fast-paced live show. His discomfort was palpable and there was only so many times he could get titters by calling contestants ‘ow’d flower.’ He even resorted to telling racist jokes in a desperate attempt to win the audience over. After only six months and the show haemorrhaging viewers, the producers returned, cap in hand, and begged Monkhouse to return. Monkhouse saw his chance and only agreed to come back if ATV would let him do a UK version of the American Hollywood Squares, which was called Celebrity Squares here. They, of course, agreed.

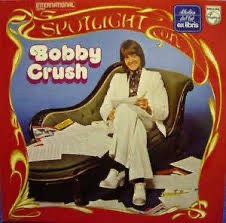

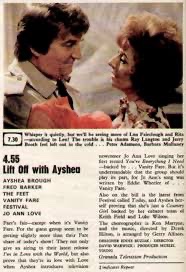

The newly revamped TGS had a jaunty new theme tune, ‘Golden Day’ by ubiquitous songster, Barry Blue (‘Dancing On A Saturday Night’. ‘Do You Wanna Dance’), whose real name is oddly Barry Green. But even with the addition of a new Golden Girl, ex-Rolf’s Young Generation and Ty-Phoo tea girl Wei Wei Wong, it was too little, too late and after a year the show had shot its bolt and was put to sleep humanely. Almost everyone growing up in the 70s watched TGS each Sunday teatime and its demise struck a chord, although maybe not at the time.

Bob, of course, never looked back and hosted a string of quiz shows including Bob’s Full House, Family Fortunes and Bob’s Your Uncle as well as the revamp of Opportunity Knocks (Hughie Green will have been spinning in his grave). He even had his own chat show and various other vehicles which he carried off with customary aplomb. But it was The Golden Shot that propelled him into the light entertainment stratosphere and for that he will always be a 70s icon, as will, of course, The Golden Shot.

And remember, hang on to your hollyhocks!