What is it that defines visually a Fellini film?

When attempting to describe a particularly chaotic scene he had witnessed, a friend once said to me, ‘It was like a Fellini film!’ Now this friend was far from being a cineaste, only visited the cinema occasionally and hadn’t even been to Italy, but he instinctively knew what a Fellini film looked like. This is true of many people who would never admit to being familiar with Italian Neo-Realism or any other style associated with cinema from that part of the world. So how do so many people know what a Fellini film looks like?

Fellini would have been 100 years old this year and, in celebration, digitally restored versions of his films have been released and are being shown at cinemas all over the world. As I watched Fellini’s Roma and La Strada as part of this centenary retrospective, my friend’s comment all those years ago came back to me. It made me realise that Fellini is one of the few directors in cinematic history whose body is work is so distinctive that a single scene or even a single frame from any of his films could be displayed and it would be immediately obvious who created it. One could also say the same thing about Picasso, Dali or Velasquez, for example, but these artists created static images. To talk about a film director in such illustrious company is rare.

So what is it about Fellini’s work that is so visually distinctive? How do people, whose interest in cinema is merely superficial, know what a typical Fellini scene looks like? To state the bleeding obvious, it’s the meticulous staging of his films, but how is this extraordinary, idiosyncratic ‘look’ created? There’s more to that than meets the eye…

Needless to say, there is no one element that, above all, creates the Fellini ‘look’ and, in no particular order, I am going to consider some the ingredients that coalesce to construct what we describe as ‘Fellini-esque.’ The scope of this article, however, is not an attempt to explain or decipher what these images necessarily mean, many critics have done this in extensive studies, although certain elements are briefly considered. But this is about the ‘look’ of a Fellini film and it is the ‘look’ that provides so much excitement and pleasure for the viewer. And it is this ‘look’ that raises Fellini above so many other artists and why so many other directors and auteurs cite him as a major influence.

Fellini began working in films with that giant of neo-realist cinema, Roberto Rossellini, and this, inevitably, influenced his earlier films profoundly. One of the tenets of neo-realism was the use of non-professional actors, a principle that Fellini stuck with throughout his career. Although he worked regularly with his principle actors, the brilliant Marcello Mastroianni and his muse (and wife) Giulietta Masina, the bulk of his cast were just ordinary people. Fellini was known to hang out in Piazza del Popolo in his adopted Rome where he would find ‘interesting’ looking people and ask them to be in his film. Who in Rome would turn down Italy’s greatest director? Fellini loved ‘grotesques’. Not grotesque in the sense of ‘ugly’ but as ‘fantastic in the shaping and combination of forms.’ Fellini’s characters were rarely the chiselled, beautiful people that usually populate films but ordinary people whose faces told a story, people who had lived through difficult times, people who Fellini saw as being uniquely Italian.

This use of compelling and engaging characters influenced a whole raft of American and European directors including Martin Scorsese, Woody Allen, Nicolas Roeg and Pier Paulo Pasolini.

The way Fellini brought these characters together in scenes and introduced them to the viewing audience was also characteristic, large, long, sometimes round, often white-powdered faces suddenly lurching from the bottom or side of the frame to take up the whole screen.

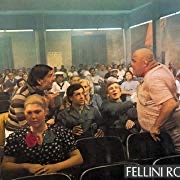

His crowd scenes were often protracted and meticulously staged with a moving camera weaving and darting between the characters, often families, as they shout, bawl, eat, drink, fight, argue, dance, romance and perform. In these scenes the seething mass of humanity is the star, this is Italian life as Fellini sees it, the common denominator by which Italy is defined.

Fellini grew up in the 1920s in Rimini on the north east coast of Italy. Like most children at this time he was, of course, brought up catholic and this inevitably had an effect on him as nuns and priests feature in most Fellini films. His treatment of them is usually comedic and often surreal. The ecclesiastical fashion show in Roma is a classic satirical moment within his body of work. But pretty much any street or crowd scene will feature a bespectacled, grim looking priest or a gaggle of bewimpled nuns, for no other reason than they were ubiquitous in Italy at the time and had a profound influence on his early life, like all Italian children from this era.. Deliberate or not, they always added an element of comedy to any scene.

Fellini’s films are clearly autobiographical, but which elements of them are fact and which are fiction has been an ongoing source of debate. Fellini was always only too happy to muddy the waters on this subject and his treatment of the clergy is no different. Whether he was being critical about religion generally or just the Catholic Church is anybody’s guess. But it certainly made for hilarious cinema when a nun or priest suddenly darted into the shot in a typically Felliniesque scene for no apparent narrative reason. in a strange sort of way it has become comic because being a Fellini film, the viewer expects a nun or priest to suddenly appear unannounced.

Fellini claims to have run away to the circus when he was a child. Whether this actually happened, no one except Fellini himself really knows, but circuses and particularly clowns appear randomly and frequently in his films in a similar way to priests and nuns. He even made one of the first ‘mockumentaries’ about his obsession with clowns for Italian TV in 1970. Any Fellini film that failed to feature clowns in some way would be disappointing. But it’s Fellini. He doesn’t need a reason to feature them.

As so much of Fellini’s output is autobiographical, there are certain settings which feature in most of his films. Growing up in the coastal town of Rimini, beaches are a recurring setting in most of his films, particularly his early ones. In La Strada, for example, the film begins and ends on a beach. 81/2, La Dolce Vita and Amarcord all include scenes on beaches.

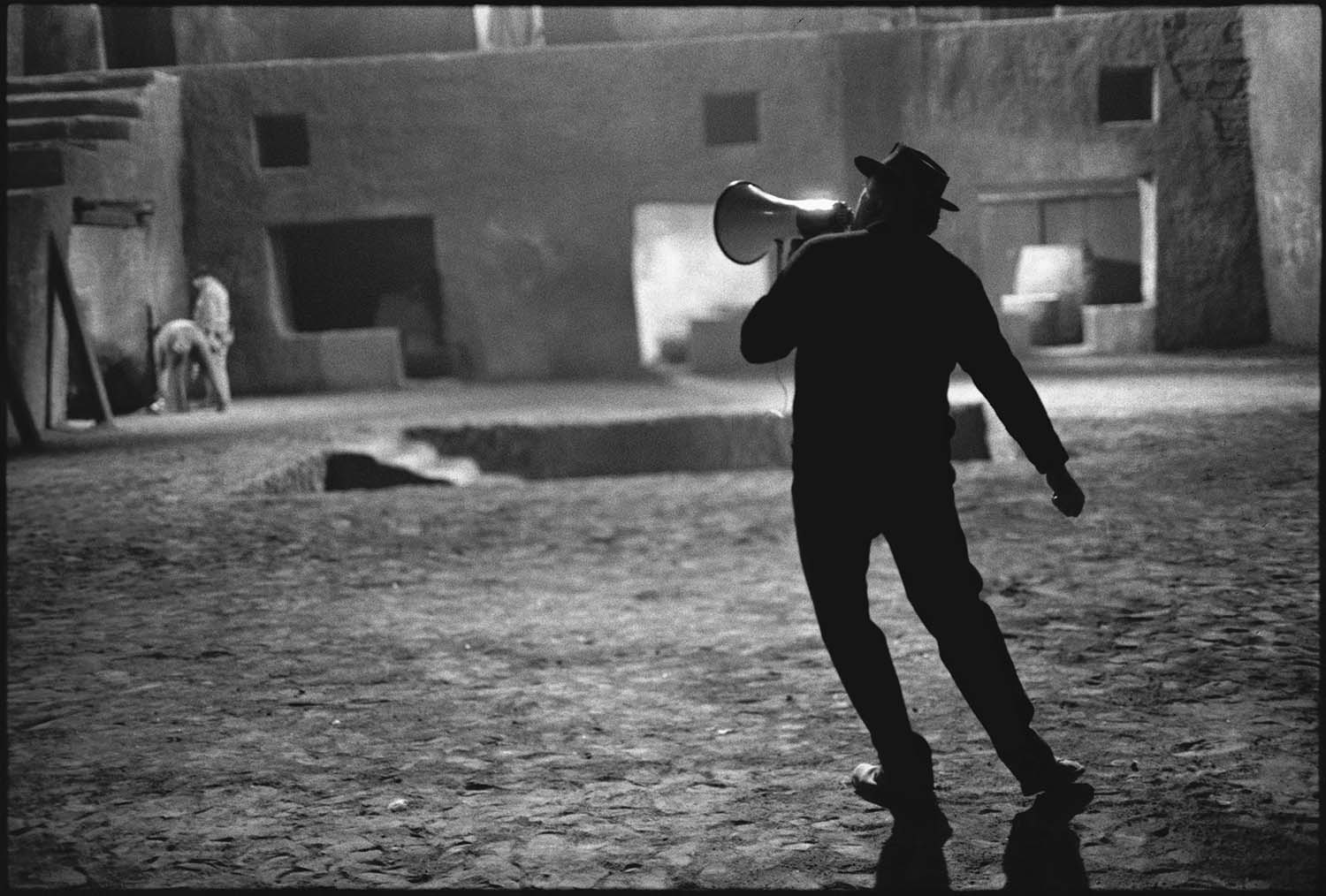

Empty night time Italian streets and piazzas are given prominence in many of his films. Often after a street has been heaving with action, humanity and life the central character is left alone to deal with their troubles, their melancholy, their dark night of the soul. With only stray dogs, a whistling wind and the harsh moonlight for company, the character reflects on their life as Gelsomina does in La Strada having run away from her harsh ‘keeper’, Zampano. The atmospheric nature of such a setting clearly struck a chord with Fellini whose tragic characters counterpointed the lively and animated nature of the crowd in the street earlier.

Strange marching brass bands, sometimes of sad looking clowns, appear unheralded and disappear again, almost punctuating important moments. In La Strada they appear in the middle of nowhere as Gelsomina sits feeling sad and sorry for herself but the musicians motivate her to return to Zampano’s act. In 81/2 they march up and down Guido’s huge white elephant of a set, partly referencing Fellini’s love of the circus and partly motivating Guido to try and move forward with his film.

Although not a visual element Fellini’s random manipulation of time is characteristic of his narratives. He may spend half an hour of a film relating the events of a few days and then jump three years ahead, for no obvious reason. Similarly, flashbacks are common and sometimes not always made obvious to the viewer. Fellini’s Roma, for example, jumps around with time, from the autobiographical past to the fictional present, and vice-versa, and back again. One might think Fellini is deliberately trying to blur the edges of time and place to create a Roma that is the one in his head, which is, of course, what the film is all about.

Fellini’s narratives can also be erratic, disordered, uneven and most certainly episodic. In Roma the young Fellini (or who we are led to believe is the young Fellini) has an encounter with a prostitute who fascinates him and he asks our out on a date and she agrees. How the date went or their relationship developed, if at all, is left unanswered. Throughout this film we jump back and forward from the main character’s (Fellini’s?) childhood to his adolescence then to the present and rarely making any sort of narrative sense. But isn’t memory just a series of disordered snapshots in our mind? His films are like this sporadic stream of consciousness and fascinating for it.

Stylistically, Fellini uses the camera to assault the viewer in the most exciting way. Extreme close-ups, aerial shots, POV shots, hand held cameras weaving their way through heaving crowds, jump cuts, long , long takes, deep focus and sweeping dolly shots pepper his films. A Fellini film can be an exhausting experience and often one viewing is nothing like enough. The meticulous mise en scene, scattergun dialogue and ultra-fast editing does not always allow the eye and brain to take in what exactly is happening in each scene. Also taking into account a Fellini film can be over two hours long, this is a mind-blowing amount of material to try and deal with in one sitting. A writer described Fellini’s films as ‘..a luxuriance of ..images‘ and, as mentioned at the start of this article, a single freeze-frame could be seen to encapsulate Fellini’s ouvre.

Fellini has been described by some commentators as ‘self-indulgent‘ and even ‘complacent‘ but in many ways, with a true auteur such as he is, these are desirable qualities and his films have never look dated or ‘uncool’. Quite the contrary. Whether their context and ideas are still relevant is, for me, irrelevant, but they look amazing and never slow down for a second. They are a visual carnival and at a time when we are being bombarded with super heroes weekly, what’s not to like?

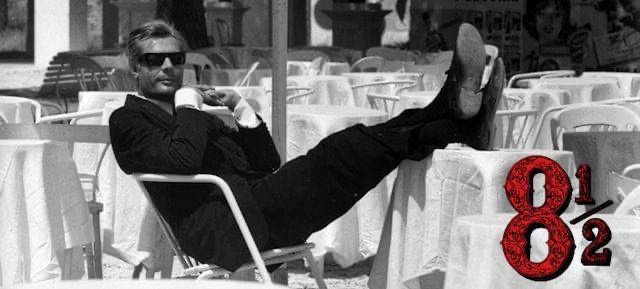

Three years ago I was on holiday in New York and stayed at a fashionable hotel in the ultra-hip Lower East Side. In the lift (or elevator as they would say) a screen showed Fellini’s masterpiece 8 1/2 on a loop 24/7. As old films go, it doesn’t come much cooler than that.

Fellini would have approved.