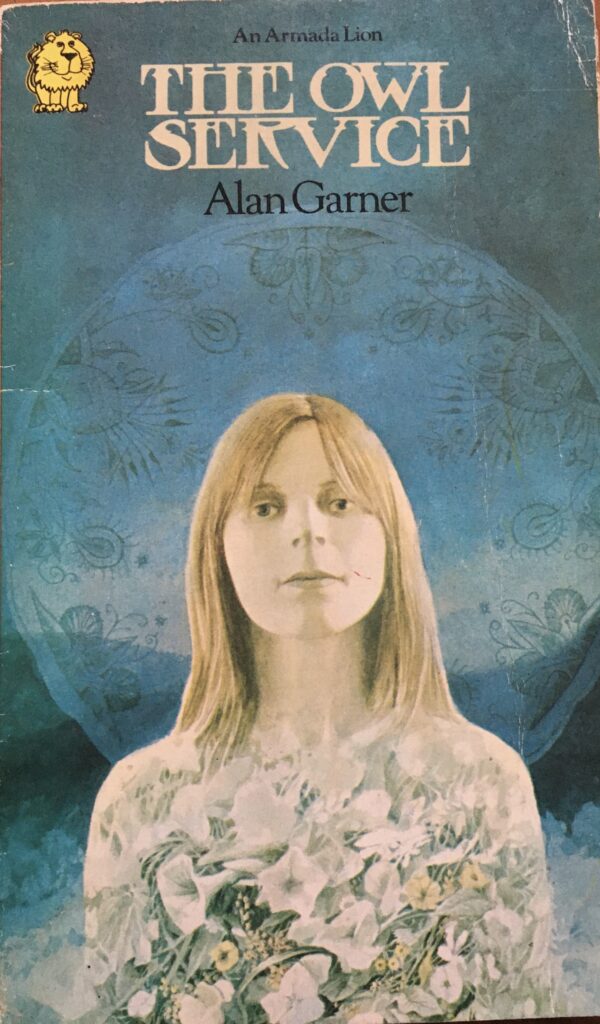

Over 50 years old and still fascinating

‘Any criticism that the series was unsuitably adult for children was untrue. Never underestimate the child; it is pure, it observes, makes its own mind up.’

Gillian Hills who played lead character Alison in the 1969 TV adaptation of Alan Garner’s almost hallucinatory novel ‘The Owl Service’ interviewed in 2008

In a nutshell Gillian Hills sums up what it is to be a child and to be exposed to narratives that are complex, challenging and often downright strange. I’ve made the point regularly that the best children’s TV was that which wasn’t made with children in mind, or anyone in mind for that matter. Many examples of this high-end entertainment already appear on these pages and will continue to appear. A shining example is the TV series of The Owl Service from a novel by the visionary and poet Alan Garner, written in 1968. A quite breathtaking children’s series through which its references to the cutting edge European directors of the time such as Antonioni, Fellini, Bertolucci and Godard and its metaphysical myriad plot lines, created a truly astonishing piece of work. The TV version of Alan Garner’s 1967 novel hit the screens in December 1969 to little fanfare. Given a prime-time Sunday teatime slot, it was clearly thought to be a worthy production by Granada. The company had lavished quite a decent budget on the serial, it was the first scripted drama to be filmed in colour by Granada and most of the filming was on location, predominantly in Wales. Ironically a technician’s dispute meant the series went out in black and white which ruined some fascinating visual imagery, although, to be fair, few people had colour TVs in 1969. To watch the series now on DVD opens up a whole new visual element to the story which is as powerful now as it was then.

At the time I was aware of a new series, a ‘children’s series, beginning at teatime on a December Sunday afternoon in 1969. There were only two channels, for god’s sake, so you were constantly aware of these things. Initially, the title did not inspire me. With my knowledge of many other ‘children’s TV series I had decided it was about a group of children (for ‘Service’ I read ‘gang’) and with ‘Owl’ in the title I had decided it was about a gang of children trying to protect or find owls. So far, so predictable. For another thing, it being Sunday afternoon, it would be something suitably anodyne and worthy, in keeping with the prevailing presbyterian establishment view of how Sundays should be observed. Swings in parks were still chained up on Sundays in 1969 remember!

Or so I thought.

It was only after I went to school the following day and had the story so far explained to me by a friend. WOW! This had to be seen to be believed. In the days before video and catch-up I had six more days to wait for episode two. And it would be nearly ten years before I’d ever have the chance of seeing episode one again. I was not to be disappointed.

The opening credits immediately created the conflicting feelings, the strangeness and the brooding, menacing atmosphere of the story. It introduced an almost other-worldly visual and metaphorical landscape. Anyone chancing upon this opening sequence with no prior knowledge of the story could be in no doubt that this was different to normal Sunday, or any other day’s, teatime fare. The juxtaposition of calm, pastoral harp music and nerve-jangling revving of, what seemed, an old motorbike along with the psychedelic visuals warned the viewer of the bumpy psychological ride which was to follow.

The themes were certainly of an adult nature: sexual awakening, jealousy, class, influence of ancient legends. But most of these were, and are, issues young people as well adults all have to come to terms with and try to understand. Of course, some children, like my 9 year-old self, would not have recognised a young girl’s sexual awakening anymore than I’d have recognised Mao Tse Tung buying 20 Bensons in the local newsagent. The Owl Service still had a profound effect on me, however. As Gillian Hills pointed out, I was hooked, fascinated and beguiled by the story and the treatment of the story. That was enough.

The story began conventionally enough. Two teenagers, Alison and Roger, are on holiday in Wales with their recently married parents. Clive, Roger’s dad , has married Margaret, Alison’s overbearing mum (who we never see). The old house has been left to Alison by her Uncle Bertram who was killed tragically in a motor cycling accident. The family are joined by Nancy, the housekeeper who had worked for Bertram years before, and her teenage son Gwyn. The seemingly deranged Huw Halfbacon, the long-time caretaker of the house, completes the cast. The narrative between the three teenagers plays out the ancient legend of Llew, Blodeuwedd, a woman created out of flowers for Llew, and Gronw, Lord of Penlynn, who Blodeuwedd falls in love with. To cut a very long story short, Blodeuwedd and Gronw plan to kill Llew but Llew kills Gronw by plunging a spear through a stone Gronw was sheltering behind and he turns Blodeuwedd into an owl for plotting against him. In many myths and legends, owls symbolise evil and owls crop up regularly throughout The Owl Service’s eight episodes. Alison discovers a tea service in the loft of her room and and creates owls out of the floral pattern on these plates, unleashing the ancient curse which had already played out between Nancy, Bertram and Huw years before.

By the time she made The Owl Service Gillian Hills was already an established actress and had led a life that was the epitome of 60s glamour and excitement. Playing the title character in the 1960 British film Beat Girl which achieved notoriety, by 1960s standards at least, in its depiction of the wild and ‘immoral’ world of teenage pop culture, The British Board of Film Censors slapped an ‘X’ certificate on it, terrified it might influence the youth of the day to revolt and maybe have a good time. Living in France with Bohemian parents she worked with Roger Vadim and Serge Gainsbourg (which young attractive French actresses didn’t?), releasing a string of hits including ‘Zou Bisou, Bisou’ which was reprised and performed by Don Draper’s girlfriend, Megan, at his birthday celebration in a memorable episode of the wonderful Mad Men.’ Two other significant film appearances were in Kubrick’s ‘A Clockwork Orange’ (See A Clockwork Orange) as one of the two girls Malcolm McDowall picks up in a record shop and as one of two girls David Hemmings romps with covered in camera film in Antonioni’s masterpiece ‘Blow Up.’ The parallels with Antonio’s post neo-realistic classic and other innovative European cinematic masterpieces such as Bertolucci’s ‘The Conformist’ and Godard’s nouvelle-vague ‘Alphaville’ with their use of extreme close-ups, jump cuts, unusual camera angles and meticulously organised staging and ’The Owl Service’ are clear.

The strangeness of the plot, the alienated characters, the long takes, the supernaturally and sexually charged atmosphere of the setting were all enhanced by the cutting edge direction giving an appropriately other-worldly quality to the production. The look and feel of The Owl Service was just so different to almost every other children’s TV series available at the time that it was almost spellbinding.

Despite Gillian Hills being 25 playing a 16/17 year old (Alison’s age is never specified) when she made The Owl Service, the eroticism of many of the scenes is striking. On a number of occasions the camera pans over her prostrate body, the red bikini she wears is symbolism that slaps the viewer across the face, the scene in which she moans at the thought of the Lady of Flowers leaves nothing to the imagination, at least nothing to an adult’s imagination… It doesn’t take a genius to work out that this is a story about a young girl’s sexual awakening. Was this appropriate material for children? Probably not but would children have worked this out? Of course they wouldn’t. But there was so much for the more thoughtful child to appreciate in this story. The way it slipped through the censors (yes they still used the repressive language of ‘censors’ in those days) net is one the many intriguing elements of this programme. It almost feels like a triumph that the faceless bureaucrats who decided what was right and wrong for people of any age to watch had, for once, failed. British children’s broadcasting was enhanced forever as a result.

The strange and dazzling camera work was one of the first things to arrest my attention. The image of Alison in her sunglasses with Gwyn and Roger reflected in each lens, the grotesque extreme close-up of the overbearing and unpleasant Nancy, the shot of Clive framed through Roger’s arm obliquely referencing the gap in the Stone of Gronwr, the tilted camera showing Clive struggling to pick up a pear which had slipped to the ground as he attempted to eat it with a knife and fork, the Wellesian deep focus in many of the internal shots. Few directors of children’s programmes took the care to create images like these.

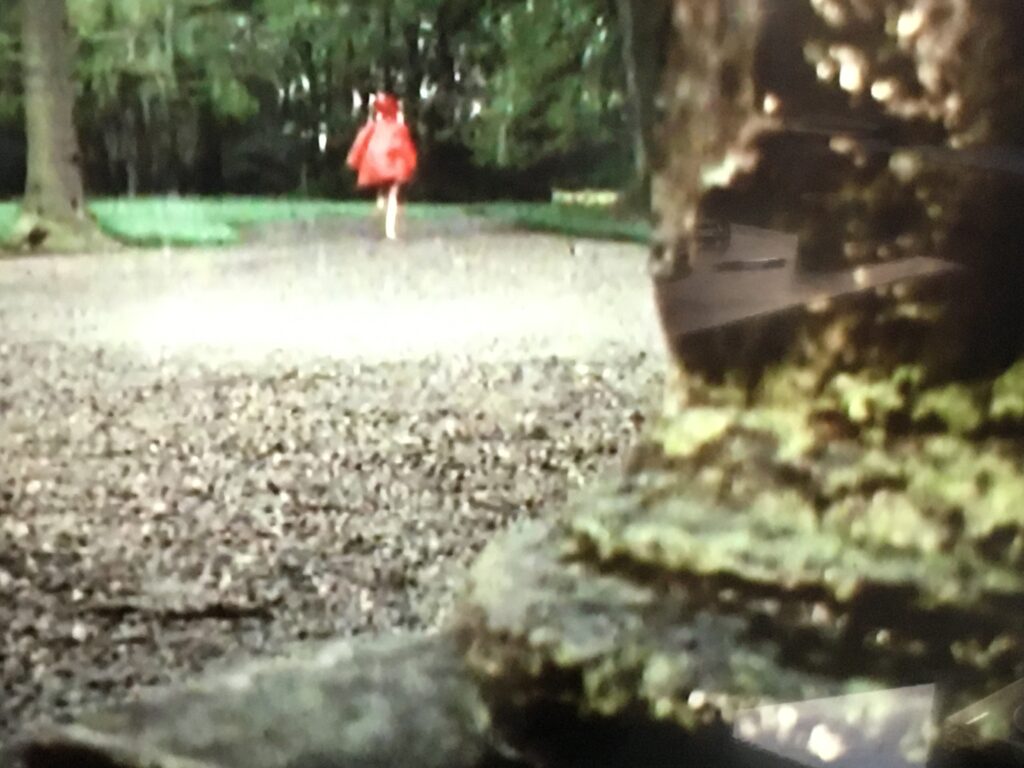

The shots of the characters reflected in mirrors, including the striking image of Gwyn and Roger in the lens of Alison’s sunglasses, was a reference to the way the legends of the valley were paralleled in present, as if parallel universes existed for the characters. An interesting device used by the director was to dress the three main characters in the electrical plug wiring colours of the time. Alison always wore red, Gwyn black and Roger green. The implication being that together they were capable of a terrifying power if unleashed. Unfortunately, a technician’s dispute in 1969 meant the episodes were broadcast in black and white meaning this reference was lost to any viewer, albeit few at that time possessed a colour receiver. It would be the 1978 repeat before any sharp-eyed members of the viewing public would be able to spot this device.

The character of Margaret, Alison’s mother, who was never seen though occasionally heard added a further mysterious element to the plot. Her tyrannical, condescending almost ghostly presence, particularly with regards to Gwyn, is conspicuous. Her role with Alison is similar to that of Nancy’s over Gwyn. Why does she forbid Alison to see Gwyn? Is it just snobbishness as he is perceived as being below Alison’s social standing? Roger uses a euphemism for snobbery to Clive, ‘Is that why Margaret’s gone so county with Alison?’, suggesting they come from a social strata way above Gwyn’s. This is further reinforced when Roger refers to joining Clive, ‘..in the business.’ Or does Margaret genuinely worry about the effect it might have on Alison as she is still a relatively and possibly impressionable teenager? Or, intriguingly, maybe Margaret is also aware of the legend and has been here before? Either way, her influence on the story is dislocating and sometimes threatening, despite her lack of corporeality.

This references to one of the main themes of the story, that of class, which resonates with the ancient legend. The Lady of Flowers falls in love with a man of a much lower standing than Llew and suffers the consequences. Nancy and Bertram’s story also echoes the ancient legend due to class and jealousy. Clearly little has moved on in the valley for over 2000 years.

A couple of interesting 1970s references to the time the series was made, crop up through the dialogue of Roger and Gwynn. While Alison, Gwynn and Roger are talking in Episode 2 Roger says ’Very inter-esting!’, a reference to a popular character played by Artie Jonson in the groundbreaking TV late 1960s comedy show, Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In, who, dressed as a cigarette-smoking Nazi, would comment on the previous sketch from behind a pot-plant with the words, ‘Very inter-esting….’ Anyone over the age of 10 at this time would be aware of this character and it eventually became something of a cliche, the number of people who would refer to it in general conversation. Rather like the number of people who used constantly irritating expressions such as, ‘Wake up and smell the coffee,’ or ‘No shit, Sherlock’ in the 2000s. They were funny for a short time.

Later Gwyn would comment, ‘You’re as daft as a clockwork orange.’ Although Kubrick’s film had not been released at this time, Anthony Burgess’s book had. There is, however, no evidence that this saying is a reference to the Burgess novel. Was it a common adage in Wales or maybe even in Alan Garner’s Lancashire? Burgess, himself was born in Lancashire and may have been aware of the saying when writing his novel. Both references, it’s fair to say, were more adult in their use although I remember clearly using the Artie Johnson line regularly at the time. It’s a small but significant element showing how the writer and director were refusing to treat their young audience as children. Bizarrely, two years later Gillian Hills would appear in Kubrick’s film of ‘A Clockwork Orange’ (See A Clockwork Orange) as one of the girls Alex picks up in the record shop. A record shop which not only displays a self-referential cover of Kubrick’s album of 2001 A Space Odyssey but also Alex’s reference to a group known as The Heaven 17. Whatever became of them, I wonder?

The final episode takes the mysteriousness and threat of the supernatural to a new level. Against a backdrop of the elements conspiring against the protagonists the rain pours down as Gwyn and Nancy leave the house and walk to the village to phone a taxi. The first half of the episode is intercut with the image of an axe chopping down what appears to be a tree. The wielder of this axe is unseen at this point. As Nancy dials for a taxi the phone box is surrounded by some Fellini-esque villagers in their sou’westers questioning her on why she is leaving. Eventually the axe wielders are revealed to be three young children and the tree is in fact the telegraph pole connected to Nancy’s telephone, stopping her from dialling out, isolating her in the village, or more importantly, Gwyn, in the village. Our last glimpse of Nancy is an elaborate long-shot from Gwyn’s point of view as she continues to rail against the world and turns on the road away from the valley. Clearly the people of the valley are only too aware of the legend and expect it to be played out again. The ambiguous ending as the three young children (the same ones who chopped down the telegraph pole?) play and lay flowers around the Stone of Gronw. Are these children the next in line to play out the legend?

In the same episode Alison becomes seemingly unwell when confronted with the ancient amulet sent to her by Gwyn. Scars appear on her face and she falls into semi-consciousness, almost into a state of sexual delirium. Roger tries to persuade Gwyn to help her but his anger is still too great and it is Roger who placates her as Gwyn weeps. But was it really Roger?

The series ends as enigmatically as it began. What goes around, comes around. Alison, Gwyn and Roger’s relationship has changed but for the better? Relationships are never straightforward, particularly teenage relationships but each character learned something, each character experienced a traumatic epiphany of some kind, what that epiphany was is for the viewer to work out. Ancient legends rarely offer straightforward answers and neither do modern relationships. But the journey to this point was mind-blowing and, as Gillian Hills rightly observed, you make your own mind up, especially if you’re a child.