Match day at Brechin’s Glebe Park

The homogeneous nature of modern stadia is just another reason why football has become so mundane

This blog may be about 60s and 70s popular culture but it is defiantly not one of those places where I moan about how crap everything is today compared to the past. That’s not to say that the 60s and 70s weren’t a golden age for comedy, music, TV and a few other things, because they were. But over the last 50 years there has been some amazing examples of all these categories as well as some absolute rubbish. It’s just the nature of things.

That said. There is one aspect of our modern cultural life that has deteriorated significantly since the 60s and 70s and although elements of it are better, something has never been replaced. Right, get to the point. I’m talking about football grounds here. You may already have read about Shoot and Goal magazines which will have given you the gist of what I’m getting at (See https://www.genxculture.com/shoot-and-goal-when-football-was-football/16/12/2019/).

In short, football clubs have lost much of their distinctiveness, quirkiness, exclusivity and, dare I say, beauty through the way their grounds have changed. I completely understand that it’s all been done in the name of safety, comfort, increase in capacity and, inevitably, increased revenues. I completely understand that but I just miss the little things, eccentricities, peculiarities and oddities as well as wonders you saw and appreciated at grounds when you attended away games. Sadly that has gone forever.

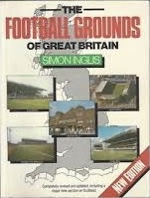

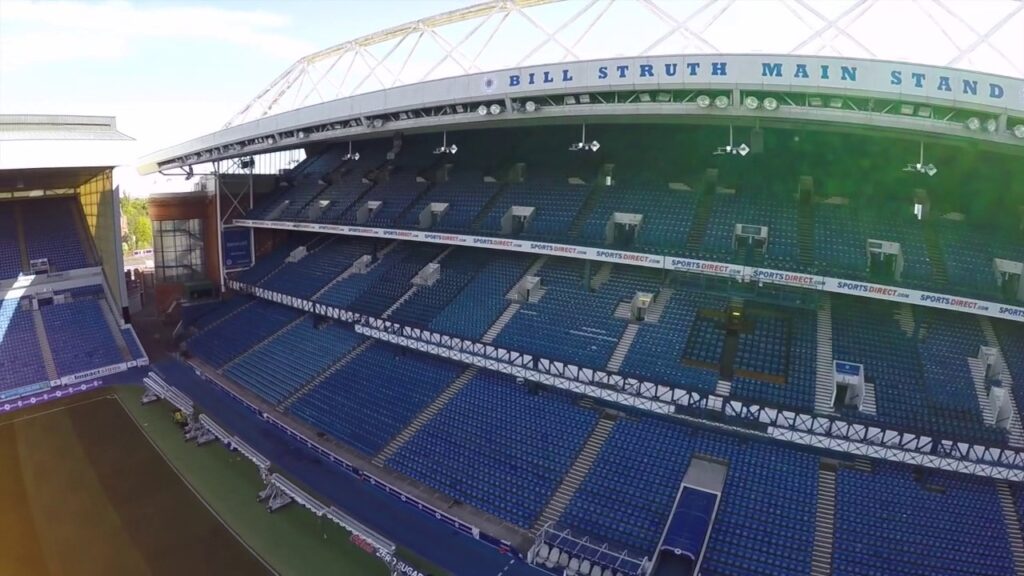

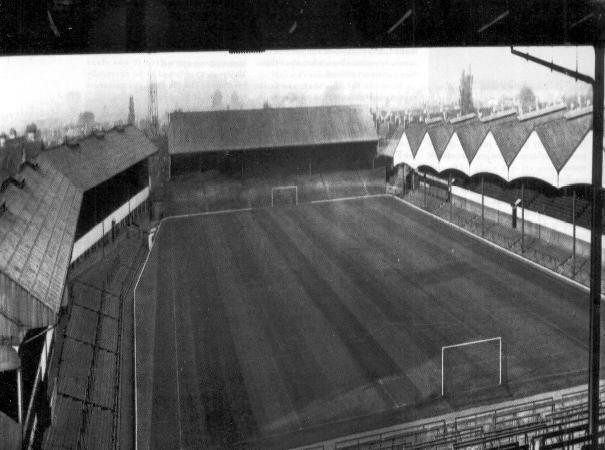

In 1983 Simon Inglis published the football stadium bible, The Football Grounds of England and Wales, updating it a few years later and adding Scottish grounds. For football ground aficionados like myself this was the Book of Revelations, the font of all football ground knowledge that you would consult before visiting a new venue. His enthusiasm and love of those quirky little features that made a ground distinctive, that added an extra layer of excitement and intrigue to any away game was infectious. These little features were the history of the club, they’d been there for maybe a hundred years or more and often became synonymous with the club’s identity. He also introduced me to the Frank Lloyd Wright of football architecture, Archibald Leitch. Born in Glasgow in 1865, Leitch designed some of the greatest and most iconic stands in British football history. Some, though criminally few, are still standing, though most of these have been redeveloped but keeping their original decoration and structure, such as Ibrox, Aston Villa, Kilmarnock, Dundee and Everton’s Goodison Park.

It’s true that few grounds still have those fascinating little distinguishing features due to redevelopment. There was a time when a game would be taking place on TV and you could tell the home team purely by the ground’s architecture. It’s still possible in some cases but not many. Uniform stands on every side of the pitch, of breeze block and corrugated steel, goal nets that all look the same (much more on this soon) and pitches that no longer even cut up, all make for a homogeneous viewing experience. Yes, it’s more comfortable, certainly safer, a higher quality of football and invariably more expensive but it’s a very different world, better in some ways, worse in many others.

I first started attending games in 1970 and still attend them today. Of the 133 clubs in the Scottish and English top leagues (134 if you still count Bury FC who were expelled from their league earlier this season) I have visited over half (76 to be precise. 79 if you count 3 teams in the English National league who have dropped out the top flights, Notts County, Chesterfield and Stockport) so I feel I have some knowledge of the subject. Out of those 79, 29 have moved to different grounds from the ones I originally attended. Of the remaining 50 most have changed their ground significantly in some way or other, usually as a result of the Taylor Report which required all top division grounds to become all-seaters. The outcome of this is that most grounds have lost their distinctive character, a few still retain a bit of their retro- charm but it’s rare. To read Simon Inglis book now is to find out what the football grounds of Scotland, England and Wales used be like.

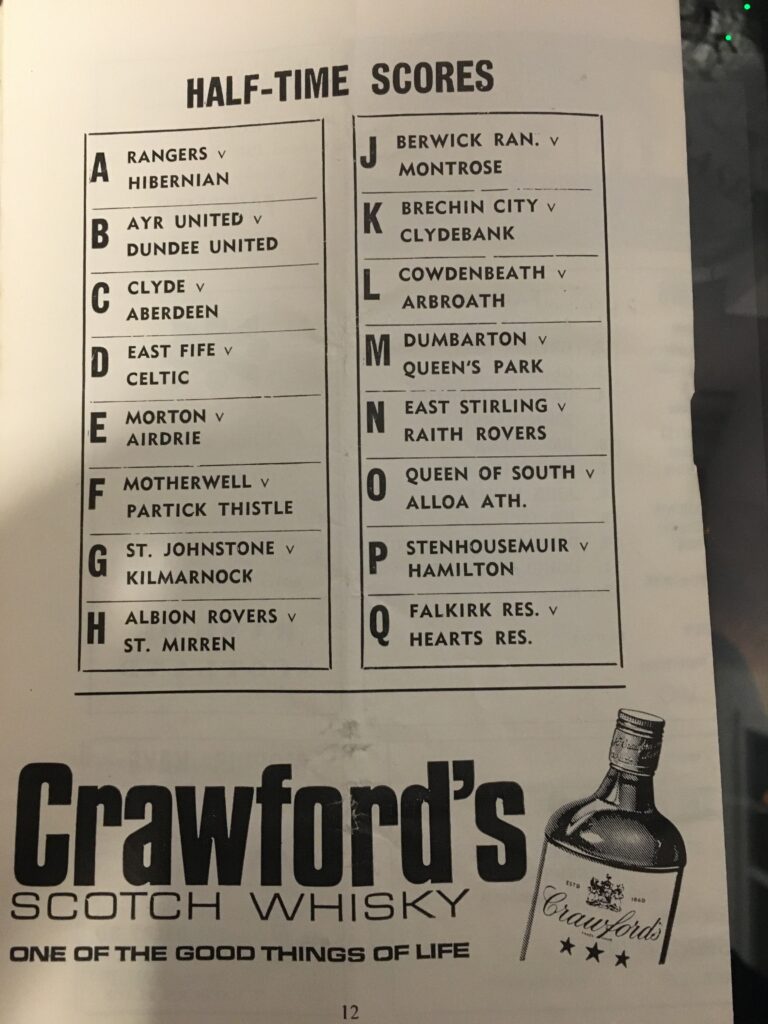

The first ground I ever attended was Tynecastle, home of my team Hearts (or to give them their Sunday name Heart Of Midlothian). The game was against St. Johnstone on August 29th 1970 and we lost 3-1. I didn’t even see our goal, a late penalty as we’d already left in (my uncle’s ) disgust. I remember vividly walking into the stadium and being completely blown away by the size of the pitch and its blinding greenness and how incredibly close we were to the action. Like many grounds of the time we had a fairly average Archibald Leitch stand (recently demolished) and banks of terracing on three sides. The open-to-the-elements standing Gorgie Road End was the largest and most interesting as it had a huge scoreboard at the back of the terracing where half time scores at other grounds would be displayed manually. The other games taking place were listed alphabetically in the programme, so you really had buy a programme if you wanted to keep abreast of half time scores. No electronic scoreboards then. In fact, we don’t even have one now. No need for such new-fangled gadgetry when a tranny in the ear will suffice.

Until redevelopment in the 1980s the tenements behind this end had one of the best views of the game from their kitchen window than probably at any other ground in the UK. They must have been sick when the first new stand was built, apart from the amount it took off the value of their properties.

Hearts’ ground now is trim, clean but still one of the most atmospheric grounds in the country. The designers, at least, maintained the close proximity of the stands to the pitch, but like so many other grounds, lacks the feeling of distinctiveness it once had. At one time you could walk along the main thoroughfare, Gorgie Road, and not even realise a football ground was there, unless you looked up a side street and saw the narrow main entrance, and, despite the redevelopment, that’s still the case.

Most top flight Scottish grounds are similar in their nondescriptness although Rangers have kept their magnificent Archibald Leitch main stand but have built on to it and their main red brick facade.

Kilmarnock are the only Premier club whose ground bears some resemblance to that of the 60s and 70s with their old stand and the floodlights perched on top of the roof, although the three other sides are relatively recent.

St Johnstone, Hamilton and Livingstone play in utilitarian stadiums with not a single feature to recommend them, built quickly and cheaply. The latter two teams even play on synthetic pitches, it’s like watching football in an oversize subbuteo ground.

In the lower divisions, however, Dundee United’s Tannadice is still quite interesting. In the 60s and 70s before redevelopment it had the steepest terracing in the country. Dizzyingly so. Anyone losing their footing would plunge about 30 feet unless their tumble was arrested by a cast iron crash barrier. Those were the days! The ground also had high walls at each corner of the pitch which displayed an advert for the good people at Skol lager. When televised a small part of this historic terracing can still be seen at the far left hand corner where the stand meets the the terracing behind the goal. They still have the same strange little stand that stretches from half way along one side of the pitch and snakes around the corner to about a third of the way behind the goal. Not that long ago, behind this same goal were allotments and a particularly poor attempt at goal will have destroyed some poor guy’s cold frame, on probably more than one occasion. It still shares the same street with its neighbour, Dundee FC‘s Dens Park which still has an original Archibald Leitch stand.

Scottish League 1 Raith Rovers’ Stark’s Park still has a lovely old fashioned Archibald Leitch stand which, like the Tannadice stand stretches part of way along one side of the pitch and round the corner behind one of the goals.. On the other side of the ground trains still pass regularly and get a fleeting view of the action.

At one time Airdrie’s Broomfield was a fantastic old fashioned stadium. Famous for its pavilion in the corner, it was reminiscent of Fulham’s Craven Cottage and Bradford Park Avenue‘s old, now abandoned, ground with its ‘Doll’s House’. Broomfield was a cauldron with a huge standing area curling two-thirds of the way around the ground. Airdrie now play at the grandly named Excelsior Stadium just outside Glasgow, but that’s all that is grand about this mundane breeze block construction.

Many lower league teams in Scotland still retain many of their old features, and, to be fair, there are some grounds I have not been to including Forfar, Albion Rovers, Stranraer and Peterhead. Of the grounds I know of Ayr United’s Somerset Park is one of the few that still looks the same as when I last visited in 1974. Although, inevitably, the forces of change are looming and plans have been drawn up to transform the ground into a stadium for ‘the future’.

A ground that will always be close to my heart(s) is Arbroath FC’s Gayfield. I attended my first Hearts away match there in 3rd November 1973. Set right on the sea front, if a beleaguered centre half wellied the ball out of the ground, it could conceivably end up in Denmark. With the exception of some covering at the once open end of the ground, Gayfield has stayed pretty much the same as when I visited for the first time all these years ago. There is one other aspect of Gayfield which I feel is worth mentioning, and will return to the fascinating subject of goal stanchions very soon.

Fir Park, the home of Motherwell FC is another ground that has little architecturally to recommend it these days but not too long ago it featured the biggest pun, probably, in world football. Across the top of what was once a covered standing area was the advice in huge block capitals, ‘Keep Cigarettes Away From The Match.’ Sadly this advice has disappeared and it now advertises some mundane loan company or something, but for many years this greeted fans weekly.

To find any quirkiness in grounds today any fan of football architecture has to forget about the top flights in both Scotland and England. In the English Premiership the top teams have spent hundreds of millions on upgrading their grounds to a level of uniform blandness, Spurs actually spent £1 billion on their recently opened new stadium. With the exception of Everton’s Goodison Park (and there are plans for them to leave soon) White Hart Lane was the last English top flight ground to retain any of its original features. Up until the 1980s it still had a white picket fence around the perimeter and for many years advertising around the pitch wasn’t allowed. Changed days. And taking centre stage was its magnificent Archibald Leitch East stand with its famous gable and its cockerel standing majestically above it. Spurs have one of the most state-of-the- art stadiums in the world now, but the character has gone.

Everton’s Goodison Park was another ground with wonderful Archibald Leitch designed stands. Its triple-tiered stand was the first of its kind. It’s still a wonderfully atmospheric stadium, something that doesn’t come across on TV. When I visited in 1998 I was pleasantly surprised by how compact it felt and how close the fans were to the pitch. Always a good sign. This three tired stand, the first of its kind, adds a real majestic quality. It’ll be a very sad day if they do leave and, like West Ham whose fans have never taken to their new stadium and the running track that separates them from the action, Everton will lose something special that Goodison provided. When footage of Goodison in the 60s and 70s is shown on TV it is noticeable that large semi-circles were created behind each goal which seemed rather odd. These were installed for safety reasons as Goodison was used as a World Cup venue in 1966. For many years I thought it added to the ground’s charm, as did the church of St Luke The Evangelist which jutted into the Gwladys Street terracing behind the goal and has now been closed off and can hardly be seen. Plans to move the club to a new stadium 2.5 miles away and have Goodison redeveloped as a residential area will rob the English Premiership of one of the last grounds of a bygone era. One final interesting fact about Goodison (well I think it’s interesting). Everton were the first club in England to install dugouts after playing a friendly at Pittodrie ( a stadium that has never had much to recommend it architecturally) against Aberdeen in 1931, who were the first team in the UK to have dugouts in their ground.

Everton’s neighbours across Stanley Park, Liverpool inhabit its famous Anfield stadium which has lacked any sort of architectural distinction since the it demolished its lovely gabled old main stand in the early 1970s. However, the sight and atmosphere of the Kop on match days was always the most distinctive part of Anfield with the banks of fans on the Kop swaying to the ebb and flow of the game like a field of poppies in the breeze.

The only other English Premiership ground of note is Aston Villa’s Villa Park. Although three sides of it are fairly ordinary, the Trinity Road stand along one side of the ground is still a sight to behold with its claret and red curved balcony wall and gable on the roof displaying the Aston Villa crest. Dating back to 1922 it’s amazing this stand has survived the mass development of 90s. Maybe if Villa had been more successful during this time it may not have.

A few clubs whose old grounds are sorely missed are Newcastle’s St James’s Park, Southampton’s The Dell and Arsenal’s Highbury. Each of those stadiums were unique for a number of reasons.

Although still on the same site St James’s Park bears no resemblance to the seething hotbed of a stadium of the 60s and 70s. Any TV footage from this time gives the impression of the fans nearly encroaching on to the pitch, and occasionally they did! The distance between the fans and the pitch was so narrow, the players could almost touch the spectators. The intimidating nature of this ground for visiting teams must have been almost palpable. As a student in Newcastle during the late 70s I attended many Magpies‘ home games but even then the stadium was being redeveloped and was hardly the bear pit it was a few years previously. The famous covered Leazes End had been ripped down and wasn’t replaced for many years, a bare wall taking its place. A flat pack stand was erected on one side although the original main stand remained until redevelopment in the 90s. But the guts had been ripped out the stadium and the team’s fortunes reflected the lack of atmosphere as they remained in the Second Division until ‘The Keegan Revolution.’

Southampton’s Dell was an amazing ground that defined the glorious differences in football grounds in the first half of the 1900s . A hotch potch of stands and bits of chaotic and disorganised terracing all within touching distance of the pitch was similar to St James’s, though smaller. With the goal nets right up against the wall of the terracing behind the goal and fans spilling over on to the narrow track, it was an exciting to place to go or even watch on telly. In 1978 the ground’s capacity was reduced to 25,000 which was probably the beginning of the end for this fantastic, atmospheric, quirky little ground. No doubt a Tesco stands in its place now.

Wolves’ Molineux was a place of beauty. Famous for its European matches played under the floodlights in the 50s, their stands were wonderful constructions. Using curves where most stands were clean straight lines, it was probably one of the most distinctive grounds in Europe. In the 1970s the club built a huge expensive new stand which almost bankrupted them and this caused the ground to fall into dilapidation. I attended a game there in 1996 and almost two-thirds of the ground was closed off with these tremendously evocative old stands rotting criminally. It was many years before the club recovered and those amazing stands stood derelict before being demolished. Wolves now have a state-of-the-art squeaky clean stadium but it’s not a patch on their glory days.

I visited Millwall FC’s The Den in their last year playing there in 1993 before moving half a mile up the road to the New Den. Talk about from the sublime to the monotonous. The Den was a classic old fashioned ground. Little stands on both sides, a covered standing area, an open standing end behind one of the goals and the players even walked on to the pitch from behind one of the goals. It was atmospheric, could be intimidating but had some great pubs two minutes walk away. A year later I visited the New Den which was one of the dullest, unatmospheric, clinical grounds I had even been to (up till then at least). I know that all clubs had to change in some way, be it for safety or comfort, but this just seemed like madness. The powers that be in the boardroom had ripped out the guts of the club in one fell swoop. The Millwall situation was the writing on the wall for many clubs, leaving their heritage, history and character behind for the sake of…what? Millwall now have a larger stadium, for me completely lacking in atmosphere or charm and where has it got them? And this is true of many, many other clubs.

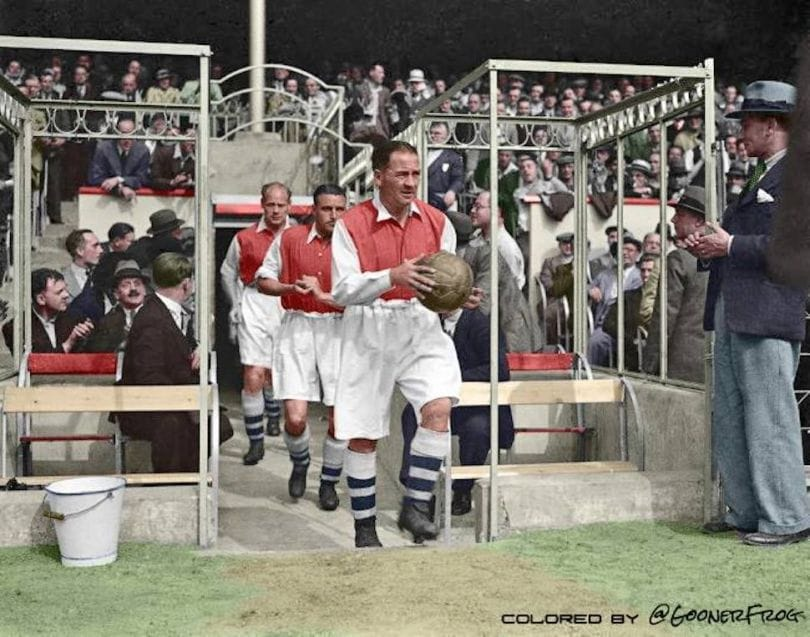

Arsenal’s Highbury was an Art Deco masterpiece situate in the middle of north London. Begun in 1931 the original Archibald Leitch stand was replaced by two almost identical stands at the east and west sides of the ground. Rather than designers Highbury was created by 1930s architects and little changed between the opening of the new stands until Arsenal left Highbury in 2006. Every wall, every, corner, nook and cranny featured some sort of Art Deco design, it’s marble halls, busts and stairways made the stadium more like a an Art Deco museum rather than a football ground. It’s tight pitch, the smallest in London, and with the fans close to the touchline, it provided an atmosphere second to none. Highbury didn’t have a dug-out. That would be too common. It had shelters, which always looked very cramped on telly and they looked more like greenhouses. But it was only the home shelter that had heating, the away shelter didn’t. Highbury even inspired a curious 1939 detective film called The Arsenal Stadium Mystery starring Leslie Banks. Filmed on location throughout Highbury, and featuring some Arsenal players of the time including manager George Allison, it tells the story of a player dropping down dead on the pitch in a match against Arsenal and the subsequent quest to find the killer after it emerges he was poisoned. Although, by all accounts, the Emirates Stadium is impressive, it could never have the style that Highbury had.

Probably the greatest football stadium ever built.

Football has gone the way of football grounds. It’s better technically, there are fewer mistakes, it’s cleaner though probably more cynical, it’s more distant, players are more skilful, and clubs are run more efficiently and clinically. Grounds are more comfortable, you can get a nice risotto or pasta dish at the kiosk, programmes are £8 and, if you really want it, you can pay for hospitality, sit in the warmth, have a three-course meal with wine and rub shoulders with captains of industry, all for a few thousand quid. That’s all fine and good, if you like that kind of thing, but I miss the roughing it, the quirky features of old fashioned grounds, the cock-ups in defence and the off-the-ball chinnings (no more of them thanks to VAR).

But if anyone wants to see grounds that still retain some unique, idiosyncratic features, it’s necessary to visit some of the lower league clubs in Scotland and England, although these are disappearing quickly. For example, Brechin City’s Glebe Park is famous for its hedge which runs along one side of the ground or the nets at Grimsby‘s Blundell Park which were donated by local fishermen, Fulham still has its ‘cottage’ and Carlisle’s Brunton Park which hasn’t changed much over the past few decades.

Over the next couple of years I’m planning to visit as many of the grounds I still haven’t been to and re-visit some of the ones that still retain a bit of charm. These venues are disappearing fast and will not be there for much longer. The inevitable forces of change are hovering over every old football ground like a zeppelin over Wembley.

So don’t hang about. We’re running out of time.