..after 50 years, a film that is still way ahead of its time.

It’s hard to convey how irresistible the desire to see Kubrick’s film of Anthony Burgess’ novel ‘A Clockwork Orange’ was for an 11 year old boy just becoming aware of grown-up literature. The only problem: it wasn’t possible to see it. Even at 15 you had an outside chance of being allowed into the cinema if the lighting was poor and your parka hood was pulled up over your head far enough. Video and DVD was a long, long way off so at 11 there were two chances. Fat and slim.

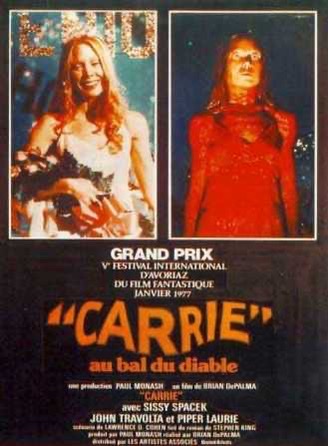

Of course the media obsession with the film, as it was with any film that skirted with the term ‘controversial’, meant plenty information to entice a pre-teenager who had just graduated on to reading the tabloids on a Sunday. Tabloids just loved ‘controversial’ films. It allowed them to take a moralistic high ground while salaciously giving every lurid detail of the sex, drug-taking, horror or violence of even the most mild of adult flicks at the local flea-pit. The Exorcist, Carrie and The Devils were three examples of films released in the early 1970s on which the tabloids poured opprobrium, described every ‘depraved’ scene and, obviously, increased the numbers of people at the box office massively. The Scottish Sunday Mail ran a double-page spread listing, helpfully, in painstaking detail, every ‘gut-wrenching’ (its words) scene for the delectation of Sunday readers. No such thing as a ‘spoiler alert’ in those days. And I particularly remember the Scottish Sunday Mail wiring Alan ‘Roughie’ Rough and his lovely catwalk model wife to a heart monitor and logged their reactions to the various shock scenes in Brian De Palma’s Carrie. The purpose, I would assume, was to show that even a Scottish international goalkeeper with supposed nerves of steel could nearly shit himself at certain scary moments in a film, so decent, god-fearing presbyterians could steer clear. In theory. In reality it just made people flock to see the film, of course. Well, that was the science bit, for what it’s worth, but it does demonstrate tabloid newspapers’ love of and obsession with ‘controversial’ films of the era.

To be fair, A Clockwork Orange actually comes across today as more disturbing because of its violence. As a society we have recognised depictions of certain types of violence, particularly towards women, as abhorrent but in 1971 references and depictions of rape, though not commonplace, were certainly more visible. Jokes about it would even be used in sitcoms. However, in the context of Burgess’ novel the violence represented in the film was intended to be shocking and to watch it now renders it probably even more disturbing than at the time of its release. Exactly what the author intended. Belonging to the Science Fiction genre, it’s set in a futuristic Britain where drugs are legal, people rarely leave their homes and violence within society has escalated. Like most Science Fiction stories it is a warning for the future.

One of the few aspects of Kubrick’s film which fails, mainly because there was no way it could have succeeded in relation to the novel, is in the character of Alex, played by 20-something Malcolm McDowell. The first half of Burgess’ novel tells the story of ultra-violent Alex and his gang of ‘droogs’ on a rampage of sex and violence. At the end of this section of the book the reader is shocked with the sudden revelation that Alex’s orgy of violence has resulted in the death of one of his victims, an old lady, and he has been arrested. It is at this point he confesses to the reader the horrifying truth, ‘And me still only fifteen.’ Here is Burgess’ warning, his reason for writing the novel and justification for the repulsive rampage of violence the reader has been subjected to. But in practical terms, this fictional narrative device could not really be depicted in the film, Malcolm MacDowell does not look anything like a fifteen year old, and social commentators did not have the intelligence to discern this.

In the early 70s there were many so called ‘controversial’ films released. It was a time of experimentation and a loosening of censorship rules. In fact, ‘censorship’ became ‘classification’ as films were seen as art and not just cheap flicks to excite the lower, uneducated classes for a couple of hours in a members-only fleapit. Therefore, films which dealt with more disturbing issues, such as violence within our automated society became a popular theme and depicted violence and sex in a brutally realistic way which the general public and ‘the authorities’, at first, found difficult to cope with. Some thought it was still there only to titilate and thereby hung the tale of A Clockwork Orange.

The violence, even though I hadn’t seen it, certainly didn’t excite me. What excited me, from what I could make out, was the futuristic look of the film, the representation of a dystopian society (something I still love) and, of course, the controversy. I still, obviously, am drawn to things the tabloids hate.

The film had been out for a few weeks before I’d even heard of it. Bizarrely, the first time I read anything about A Clockwork Orange was in the pages of Shoot, the adolescent weekly football magazine ( see Shoot and Goal Magazine: When Football Was Football and Not Just A ‘Product’), more precisely in Everton and England footballer Alan Ball’s weekly column. The content of this column was unstintingly dull. After he had given his ghost-writer details of Everton’s most recent match it was a desperate struggle to find anything else to say to reach the required 500 words. Often the interviewer will have asked Alan, so what else did you do this week? The terminally boring life of a professional footballer was laid bare in these columns but one week in 1971 Al and his lovely wife, Lesley, went to see A Clockwork Orange. His critical conclusion, summed up in a sentence, was that he ‘slept through it.’ The moral question of whether a top footballer should have been discussing, no matter how curtly, a film he had seen about teenage ultra-violence, drug-adulterated milk bars, under-age sex, gang warfare and rape is by the by, it was the 70s after all. But I do have Alan Ball to thank for alerting me to this cult classic. I immediately decided to find out about this film, why would Alan Ball be referring to it if it wasn’t culturally important (or 11 year old words to that effect)?

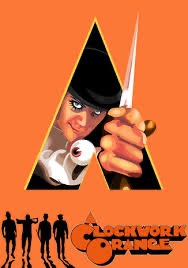

I began to notice the iconic film poster with a cartoonesque Alex brandishing a knife through a triangle, a naked woman kneeling below the apex (always irresistible to an 11 year old), an eyeball sitting on his outstretched arm and, most intriguingly, the bowler hat and false eyelash on one eye! The futuristic typeface added a further appealing element to the whole package. This was seriously alluring.

My fascination was further enhanced (if that was possible) when I actually managed to see an extract from the film. STV, at this time, had a film review programme which was broadcast at 10.30pm once a week called Cinema. Presenters of this programme included Michael Parkinson, Clive James and Robert Kee, and I think it was Parkie who showed a clip of A Clockwork Orange much to my excitement. In those days, obviously, there was no video recording so the 20 second black and white extract featured Alex and his Droogs racing through country lanes in a stolen sports car, this absolutely classic Kubrickian moment is indelibly stamped on my memory. This moment only cemented my fascination with the film and my frustration of not being able to see it.

I only have vague memories of the media outrage about the copycat violence which they claim broke out as result of young people having their minds ‘warped’ by the movie. It was certainly a particularly strong defence in cases of extreme violence at the time, irrespective of whether there was any truth in it. Buttoned-up Establishment British judges were only too happy to accept the possibility that some depraved modern film might be the reason for our kids’ aggression. Clearly society couldn’t be to blame.

The ‘look’ of the film certainly did influence young people. I do remember Crombie coats, Doc Marten’s boots and even the occasional false eyelash manifesting themselves in our high streets. Most of them daft wee laddies (and a few lassies) who just thought they looked cool but would have run a mile if anyone challenged them to a ‘bitva’! The media shitstorm, however, was enough for Kubrick to withdraw the film in the UK in 1973 and it remained unshown publicly in the UK until the director’s death in 1999. Rumour had it that a cinema in Paris showed it throughout the 70s, 80s and 90s.

The film’s iconic resonance has been enshrined by the fact that so many images are as well-known now as they were then. Certain words from Nadsat have found their way into common usage, for example ‘horrorshow ( The Scars anyone?)’, ‘ultraviolence and ’droog’. ‘Moloko’ which was based on the Russian word for milk, and in the film is a narcotic-filled milk drink, became the name of a successful 90s band, as did Heaven 17, whose name is mentioned and shown in the record shop scene when Alex meets two girls whilst browsing in the store. Echo and the Bunnymen’s record label was entitled ‘Korova’ after the milk bar frequented by Alex and his droogs and let’s not forget about Glasgow’s underground transport system punningly named ‘The Clockwork Orange’.

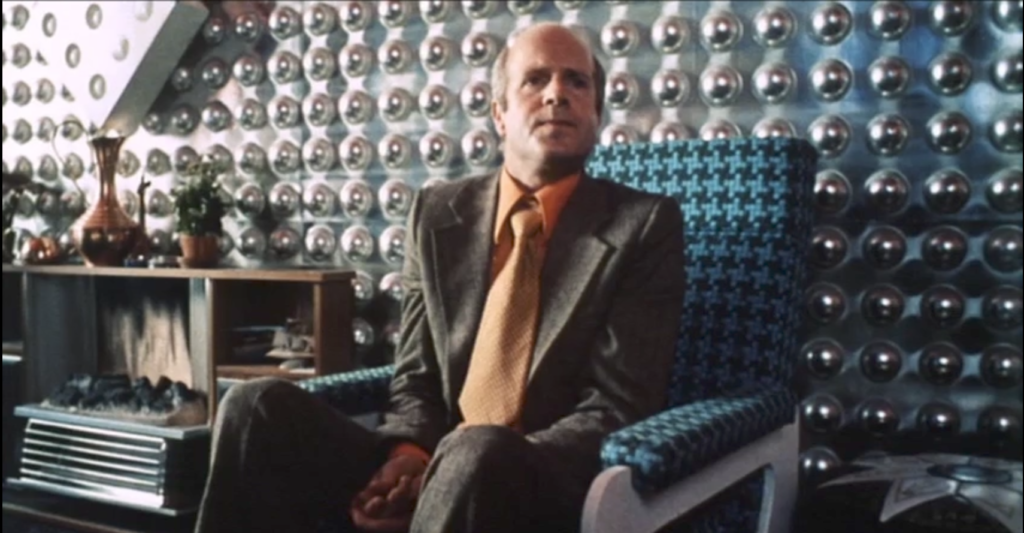

As Kubrick preferred to work in the UK, many of the actors in his films were familiar faces to British TV viewers as well as film-goers. Philip Stone, who appeared in three Kubrick masterpieces (more than any other actor apart from Joe Turkel), a fine jobbing actor who had appeared in countless TV productions since the early sixties, played Alex’s dad. Stone’s performance clearly resonated with Kubrick as he went on to appear in Barry Lyndon and, in his crowning achievement, as the Overlook Hotel’s former caretaker, a role in which he excelled as the courteous but terrifying Delbert Grady ( See Kubrick’s Smoke and Mirrors: 50 Years of The Shining ). A Clockwork Orange was also a huge break for the young Warren Clarke as one of Alex’s droogs, Dim. Like Malcolm McDowall and Philip Stone, Clarke went on to work in a range of prestigious productions not least with Lindsay Anderson in O’ Lucky Man. The lovely Adrienne Corri, like Stone a stalwart of quality TV productions, played the brutally assaulted wife of the writer, Patrick Magee. It was the writer, Mr Alexander, who, in the novel, told of the idea of a clockwork orange, a speech which, oddly, failed to make it into the completed film. Magee was a favourite actor of the great Samuel Beckett who wrote one of his greatest plays, Krapp’s Last Tape, specifically for Magee. Also popping up in the film was John Savident, another prolific British actor who ended his professional life as Foghorn Leghorn-like butcher Fred Elliott in Coronation Street. Having played in Shakespeare productions, many Wednesday plays and, of course, in A Clockwork Orange, it is Corrie, sadly, he will be remembered for by most people. That said, he did appear in 714 episodes, I say, 714 episodes! Michael Bates, best known as Blamire, one of the original characters on Last of the Summer Wine, is excellent as the sadistic prison officer (‘Shut your bleeding’ hole!’). He also appeared in every episode of It Ain’t Half Hot, Mum but the less said about that… Miriam Karlin as the cat lady, who comes to a nasty end at the hands of Alex, was well known for The Rag Trade (with a young Reg Varney!) and a fledgeling Steven Berkoff as a copper are just a few of the familiar faces, many of whom possibly didn’t realise just how much their parts were going to cement their reputations in the years to come.

The excellent and Kubrick favourite Philip Stone

Why does A Clockwork Orange still fascinate nearly 50 years later? Because, like so many Kubrick films, it looks ageless but futuristic, depicting a parallel universe which hasn’t been defined by the fashions of the time but clearly showed a world that is still ‘ours.’ The electronic Wendy Carlos soundtrack, the meticulous whiteness of the sets, the flowing strangeness of the typefaces, the sweeping camera shots, Alex’s direct looks into the camera (unusual for the time), Burgess’ ‘Nadsat’ argot as spoken on the voiceover by Alex, all come together to create a representation of such stunning originality that only an auteur like Kubrick could have had such vision.

And above all, to the curious teenager, it was an ‘X’. That most fascinating of all letters whose cultural cache is so much heftier than the dull old literal ’18.’ Here was a tantalising world almost within touching distance that held secrets open only to adults, who we were to assume had the intellect and maturity to cope with such esoteric and supposedly disturbing subject matter. Kubrick’s dystopian vision proved too much, however, for an adult population weaned on the hypocritical outrage of the tabloids, Mary Whitehouse and so-called public-decency. But for a short time in the early 70s A Clockwork Orange was the most state-of-the-art, modern, challenging and iconic artefact of its age.

Despite the fact the concept of a clockwork orange is never even mentioned in the film.